Managing RSV

Currently, treatment of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is limited to symptomatic management, and off-label use of the antiviral ribavirin. While a prophylactic treatment is available for paediatric populations at high risk of severe RSV, no preventative therapies are available for adults. Discover:

- Limitations of current options and how to overcome these

- Investigational vaccines in adult populations

- Developments in antiviral treatments

Unmet needs for managing RSV

There is no approved treatment for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and preventative therapies are limited to infants and children at high risk of severe RSV infections1. There is an urgent requirement for preventative therapies that robustly protect vulnerable adult populations to reduce hospitalisations and mortality.

Unmet needs in RSV treatment

There are no approved treatments for RSV in children and adults who have severe infections

The antiviral drug ribavirin is used off-label for the treatment of life-threatening RSV in patients with dysfunctional immune systems2,3. Ribavirin is restricted to this patient population as it is associated with toxicities affecting multiple body systems, including psychiatric and haematological effects3. Further, ribavirin has limited clinical evidence of efficacy in RSV; one study reported no efficacy in reducing admissions to intensive care, lengths of hospital stays, the use of ventilatory support, or mortality, while a second study showed that ribavirin reduced the likelihood of upper respiratory tract infections progressing to lower respiratory tract infections2,4. Ribavirin must be administered as an aerosol for RSV infections, which also restricts its widespread use3.

Therefore, management of RSV infections is reliant on symptomatic relief of bronchiolitis, bronchitis and pneumonia5. Severely affected patients might need ventilatory support in intensive care2. More targeted treatment options are needed to manage RSV.

Unmet needs in RSV prevention

There is only one prophylactic option for RSV, which is for use in infants and children only; there are no prophylactic options for adults

The prophylactic treatment, palivizumab, is indicated for the prophylaxis of RSV in infants and children who are at high risk of severe RSV infections.

Palivizumab is a monoclonal antibody that is administered by monthly intramuscular injection during the RSV season1. This type of treatment is known as passive immunisation, as it supplies high-risk individuals with antibodies, but does not induce an immune response to RSV.

Palivizumab is indicated for use in1:

- Premature infants (born ≤35 weeks) under the age of 6 months at the start of the RSV season

- Children less than 2 years of age who have required treatment for bronchopulmonary dysplasia (chronic lung disease) in the last 6 months

- Children less than 2 years of age with haemodynamically significant congenital heart disease

A systematic review has shown that palivizumab reduces rates of hospitalisation for RSV infection in these at-risk paediatric populations6.

More preventative therapies are needed, especially for high-risk adult populations1.

RSV prevention in adults

As there are no preventative treatments for adults at risk of severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), ongoing vaccine trials may be of interest to clinicians involved in managing the burden of RSV2.

Challenges of developing vaccines for older adults

One of the challenges of developing vaccines for older adult populations is that the aging immune system is not as responsive as that of younger populations7.

Vaccines developed for older people must be tailored to produce an immune response of an appropriate magnitude7

The main goal in adults is to deliver an appropriate dose of antigen to provoke a sufficient immune response7. Strategies to maximise the immune response to a vaccine could include the use of adjuvants (additives that boost the immune response to the antigen in the vaccine), the inclusion of multiple viral antigens or the delivery of booster vaccinations7.

Adults aged over 65 years will also vary in the number of times they have been infected with RSV, which may affect immune responses to the vaccine7.

Vaccine strategies in adults

Several strategies may be used in the development of RSV vaccines.

Live-attenuated vaccines7

- Based on a live virus, but with a reduced ability to cause harm

- Effectiveness of live-attenuated viruses is based on pre-existing immunity

Recombinant vector vaccines5,7,8

- Utilise a different type of non-harmful virus, such as the adenovirus, as a vector to transport portions of target DNA from the virus of choice

- Following vaccination, the target DNA is translated into an antigen, which provokes an immune response

- The adenovirus vector may also possess adjuvant properties, boosting the immune response in older people

Subunit vaccines7,8

- Comprise purified, antigenic proteins of the virus only

- Allow delivery of a higher antigen dose compared with whole-virus, so may be appropriate for use in older adults

Nanoparticle vaccines7–9

- Use virus-like particles or vesicles to deliver viral proteins, or DNA or messenger RNA (mRNA) that is converted to antigens by the vaccinated person

- mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 provoke similarly sized immune responses in adults of all ages

RSV antigens in investigational vaccines

The majority of investigational vaccines are based on the F protein of RSV5. The F protein is present on the surface of RSV, and in comparison with the G protein, the F protein is much less variable5,7,10.

The structure of the F protein changes once it fuses to the cells of a human host; the different forms are termed prefusion F and postfusion F. The immune response is greater against prefusion F than postfusion F, so investigational vaccines tend to focus on the prefusion F structure to provide optimal protection against RSV infection5,7.

The inclusion of other antigens of RSV, such as the G protein, M2-1 protein and N protein within a vaccine can bolster the immune response.

Investigational RSV vaccines in older adults

Several Phase II and Phase III clinical trials of RSV vaccines in adults aged 60 years or over are currently ongoing or have completed (Table 1). These vaccines are based on several of the RSV protein components (Figure 1). Studies in other populations, such as children and pregnant women, are also ongoing2,8.

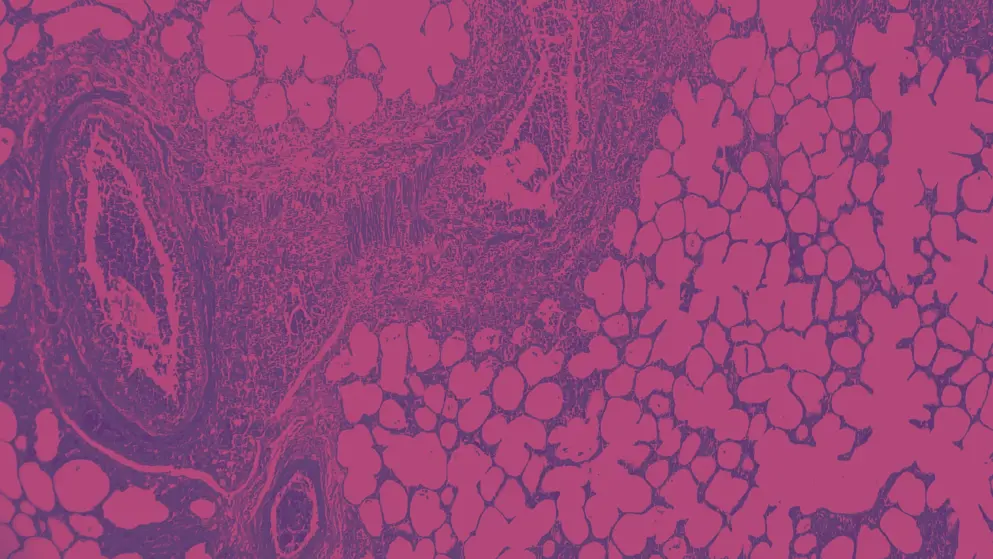

Figure 1. RSV protein targets for investigational vaccines in adults aged over 60 and investigational antivirals7. RSV, respiratory syncytial virus

Table 1. RSV vaccine trials in adults aged 60 years or over. Individual trials do not incorporate multiple RSV vaccines and data shown are not intended to be compared across studies5,7,11–19. AE, adverse event; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

| *Adults aged over 55 years †Phase III studies are expected ‡A Phase III trial in adults aged 60 years or over is underway (NCT04908683) |

|||

| Vaccine, trial identifier and status | Trial Phase | Efficacy results | Safety results |

| ResVax (NCT02608502) Completed March 2016 |

III | No reduction in numbers of patients with lower respiratory tract infections caused by RSV | — |

| MVA-BN-RSV* (NCT02873286) Completed December 2018 |

II | Neutralising antibody and T-cell responses, with a booster increasing responses | — |

| Ad26.RSV.preF in combination with the influenza vaccine Fluarix (NCT03339713) Completed July 2018 |

IIa | Robust neutralising and binding antibody responses No interference between vaccines |

AEs were generally transient, and mostly mild or moderate Most frequently reported AEs were injection site pain, fatigue, myalgia, headache, chills and arthralgia |

| GSK3844766A† (NCT03814590) Completed December 2020 |

I/II | High levels of neutralising antibodies Larger immune responses with adjuvant than without |

Most AEs were mild or moderate Most frequently reported AEs were injection site pain, fatigue and headache |

| Ad26.RSV.preF† (NCT03982199) Due to be completed in May 2024 |

IIb | Reduced onset and reduced worsening of RSV symptoms | Most AEs were mild or moderate The most common AEs were fatigue, myalgia and headache |

A key requirement of vaccines for older people is the need to overcome the reduced immune response in comparison with younger populations.

Indeed, the investigational GSK3844766A vaccine has shown similar responses across adults of all ages, indicating that the reduced immune responses in older people can be overcome14.

The investigational Ad26.RSV.preF vaccine has shown that symptom onset and severity can be reduced; initial data are from a single RSV season, but these results indicate that the reported immune responses to vaccines do translate into a positive symptom-based outcome12.

Larger studies may be needed to identify vaccines that reduce RSV hospitalisations and mortality, and to determine the most effective dosing schedules

As vaccine trials continue, it will also be important to consider the timing of the vaccination and the need for boosters to ensure adequate protection during the RSV season7. The seasonality of RSV also raises a requirement to consider the timing of RSV vaccinations alongside other seasonal vaccinations, such as that for influenza. While cohort sizes for RSV and influenza trials are small, and additional noninferiority studies are required for approval of coadministration of RSV and influenza vaccines, larger studies are ongoing5. As the impact of RSV is similar to or greater than that of influenza, and both infections are seasonal, a combined approach to vaccination may be appropriate20–23.

As the RSV vaccine landscape develops, new vaccines might emerge to prevent severe RSV infection in adults, as palivizumab does for infants and children

Treating RSV infections

Treatment goals for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are to relieve symptoms, reduce the time until symptoms are resolved, reduce viral load and limit transmission2.

Current management strategies for RSV

As there is no licensed treatment for RSV, and the use of ribavirin is restricted to immunocompromised patients, most patients with RSV will only receive measures to manage symptoms2,3

The symptomatic management of the outcomes of RSV – bronchiolitis and pneumonia - may occur at home in mild cases, and involves24,25:

- Hydration

- Relief of fever with antipyretics

- Pain relief

- Saline nasal drops for infants and children

Severe cases of RSV require acute treatment in a hospital or intensive care setting, with intravenous fluids, supplementary oxygen, ventilatory support and suctioning of the airways2,24–26. Patients may also be treated with antibiotics in the absence of a diagnosis of RSV27,28.

As these treatments do not target the cause of the infection, there is a need for novel antiviral therapies that are suitable for use across a broad patient spectrum.

Investigational antivirals in adults

A number of investigational antiviral therapies are in development, which can be classified as2,3:

- Fusion inhibitors

- Target entry of RSV into host cells and fusion of RSV-infected cells with healthy neighbouring cells

- Replication inhibitors

- Target replication of RSV and the assembly of new viruses within host cells

As with vaccines, most antivirals in development target the F protein of RSV, as it is less variable than the other component proteins of RSV (Figure 2)2. Other targets include the L protein, and the N protein, which have roles in replication29,30.

Figure 2. RSV protein targets for investigational antivirals7. RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Investigational antiviral treatments in clinical trials have only demonstrated efficacy when initiated prior to symptom development. As RSV progresses through the respiratory tract, it may become more difficult for antiviral drugs to have a positive impact on infected cells2.

Five investigational oral antivirals and one investigational inhaled antiviral have recently completed or are currently in Phase II trials in adults (Table 2). Studies in other populations, including infants, are also ongoing2.

The investigational drugs listed in Table 2 are not yet at the Phase III clinical trial stage and so it may be some time until the drugs are available to patients in routine practice

Table 2. Investigational antivirals for RSV in adults. Individual trials do not incorporate multiple antivirals and data shown are not intended to be compared across studies31–40. AE, adverse event; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SAE, serious adverse event; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection.

| *Further study ongoing in patients who have received stem cell transplants (NCT04267822) †Further study ongoing in adolescents and adults who have received stem cell transplants (NCT04056611) ‡Inhalation antiviral. A trial in stem cell patients was terminated in 2019 (NCT03715023) **Further study in patients who have received stem cell transplants are ongoing with upper respiratory tract infections and patients (NCT04633187) |

||||

| Drug, trial identifier and status | Phase | Patient population | Efficacy results | Safety results |

| RV521* (NCT03258502) Completed October 2017 |

II | Healthy adults with RSV | Decreased viral load and nasal secretions | No treatment-related SAEs |

| GS-5806 (presatovir) (NCT02254408; NCT02254421) Completed July 2017; Completed April 2017 |

II | Stem cell transplant recipients with URTI caused by RSV - Stem cell transplant recipients with LRTI caused by RSV |

No decrease in viral load or progression to LRTI - No decrease in viral load |

AEs were similar for presatovir and placebo - AEs were similar for presatovir and placebo |

| JNJ-53718678† (rilematovir) (NCT02387606) Completed October 2015 |

IIa | Healthy adults with RSV | Decreased viral load, duration of viral shedding, nasal secretions and disease severity | Most AEs were mild or moderate |

| PC786‡ (NCT03382431) Completed May 2018 |

I/II | Healthy adults with RSV | Decreased viral load, nasal secretions, and disease severity | Well-tolerated |

| EDP-938** (NCT04196101) Due to be completed in April 2022 |

II | Healthy adults with RSV | Decreased viral load and nasal secretions | Most AEs were mild |

References

- Synagis summary of product characteristics, 2021. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6963/smpc. Accessed 20 September 2021.

- Domachowske JB, Anderson EJ, Goldstein M. The future of respiratory syncytial virus disease prevention and treatment. Infectious Diseases and Therapy. 2021;10:47–60.

- Simões EA, Bont L, Manzoni P, Faroux B, Paes B, Figueras-Aloy J. Past, present and future approaches to the prevention and treatment of respiratory syncytial virus infection in children. Infectious Diseases and Therapy. 2018;7(1):87–120.

- Shah DP, Ghantoji SS, Shah JN, el Taoum KK, Jiang YJ, Popat U, et al. Impact of aerosolized ribavirin on mortality in 280 allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients with respiratory syncytial virus infections. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2013;68(8):1872–80.

- Sadoff J, de Paepe E, Haazen W, Omoruyi E, Bastian AR, Comeaux C, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the Ad26.RSV.preF investigational vaccine coadministered with an influenza vaccine in older adults. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2021;223(4):699–708.

- Homaira N, Rawlinson W, Snelling TL, Jaffe A. Effectiveness of palivizumab in preventing RSV hospitalization in high risk children: A real-world perspective. International Journal of Pediatrics. 2014;2014:1–13.

- Stephens LM, Varga SM. Considerations for a respiratory syncytial virus vaccine targeting an elderly population. Vaccines. 2021;9(6):624.

- Shan J, Britton PN, King CL, Booy R. The immunogenicity and safety of respiratory syncytial virus vaccines in development: A systematic review. Influenza and other Respiratory Viruses. 2021;15(4):539–551.

- Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Widge AT, Jackson LA, Roberts PC, Makhene M, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccine in older adults. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383(25):2427–38.

- Vandini S, Biagi C, Lanari M. Respiratory syncytial virus: The influence of serotype and genotype variability on clinical course of infection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017;18(8):1717.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. A study of an Ad26.RSV.preF-based regimen in the prevention of reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)-confirmed respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-mediated lower respiratory tract disease in adults aged 65 years and older (CYPRESS). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03982199?term=NCT03982199&draw=2&rank=1. Accessed 20 September 2021.

- Falsey A. Efficacy and immunogenicity of an Ad26.RSV.preF-based vaccine in the prevention of RT-PCR-confirmed RSV-mediated lower respiratory tract disease in adults aged ≥65 years: A randomized, placebo-controlled, Phase 2b study. IDWeek 2021; Abstract LB14. 2021.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. A study to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of seasonal influenza vaccine and an adenovirus serotype 26-based vaccine encoding for the respiratory syncytial virus pre-fusion F protein (Ad26.RSV.preF), with and without co-administration, in adults aged 60 Years and older in stable health. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03339713?term=NCT03339713&draw=2&rank=1. Accessed 20 September 2021.

- Ruiz Guinazu J, Tica J, Andrews CP, Davis MG, de Smedt P, Essink B. A respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F protein (RSVPref3) candidate vaccine administered in older adults in a Phase I/II randomized clinical trial is immunogenic. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2020;7(Supplement 1):S188-9.

- Tica J, Ruiz Guinazu J, Andrews CP, Davis MG, Essink B, Fogarty C. A respiratory syncytial prefusion protein (RSVPreF3) candidate vaccine administered in older adults in a Phase I/II randomized clinical trial is well tolerated. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2020;7(Supplement 1):S187-8.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. A study to assess the safety, reactogenicity and immune response of GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) biologicals’ investigational respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine (GSK3844766A) in older adults, 2020. hhttps://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03814590?term=NCT03814590&draw=2&rank=1. Accessed 20 September 2021.

- Jordan E, Lawrence SJ, Meyer TPH, Schmidt D, Schultz S, Mueller J, et al. Broad antibody and cellular immune response from a phase 2 clinical trial with a novel multivalent poxvirus-based respiratory syncytial virus vaccine. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2021;223(6):1062–72.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. A study to evaluate the efficacy of MEDI7510 in older adults, 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02508194?term=NCT02508194&draw=2&rank=1. Accessed 20 September 2021.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. A study to evaluate the efficacy of an RSV F vaccine in older adults, 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02608502?term=NCT02608502&draw=2&rank=1. Accessed 20 September 2021.

- Ackerson B, Tseng HF, Sy LS, Solano Z, Slezak J, Luo Y, et al. Severe morbidity and mortality associated with respiratory syncytial virus versus influenza infection in hospitalized older adults. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2019;69(2):197–203.

- Falsey AR, Hennessey PA, Formica MA, Cox C, Walsh EE. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Elderly and High-Risk Adults. Exp Lung res. 2005;31(Suppl 1):77.

- Sieling WD, Goldman CR, Oberhardt M, Phillips M, Finelli L, Saiman L. Comparative incidence and burden of respiratory viruses associated with hospitalization in adults in New York City. Influenza and other Respiratory Viruses. 2021;15(5):670–7.

- Chatterjee A, Mavunda K, Krilov LR. Current state of respiratory syncytial virus disease and management. Infectious Diseases and Therapy. 2021;10:5–16.

- NHS. Treatment of bronchiolitis, 2018. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/bronchiolitis/treatment/. Accessed 20 September 2021.

- NHS. Treatment of pneumonia, 2019. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/pneumonia/treatment/. Accessed 7 October 2021.

- Young M, Smitherman L. Socioeconomic impact of RSV hospitalization. Infectious Diseases and Therapy. 2021;10:35–45.

- Hanson KE, Azar MM, Banerjee R, Chou A, Colgrove RC, Ginocchio CC, et al. Molecular testing for acute respiratory tract infections: Clinical and diagnostic recommendations from the IDSA’s diagnostics committee. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020;71(10):2744–51.

- Zhang N, Wang L, Deng X, Liang R, Su M, He C, et al. Recent advances in the detection of respiratory virus infection in humans. Journal of Medical Virology. 2020;92(4):408–17.

- Collins PL, Melero JA. Progress in understanding and controlling respiratory syncytial virus: Still crazy after all these years. Virus Research. 2011;162(1–2):80–99.

- Collins PL, Fearns R, Graham BS. Respiratory syncytial virus: Virology, reverse genetics, and pathogenesis of disease. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 2013;372:3–38.

- Coakley E, Ahmad A, Larson K, Mcclure T, Lin K, Tenhoor K. A novel RSV N-inhibitor, administered once or twice daily was safe and demonstrated robust antiviral and clinical efficacy in a healthy volunteer challenge study. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2019;6(Supplement 2):S995.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. A study to assess EDP-938 for the treatment of acute upper respiratory tract infection with respiratory syncytial virus in adult subjects (RSVP), 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04196101?term=NCT04196101&draw=2&rank=1. Accessed 30 September 2021.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. A study of PC786 to evaluate the antiviral activity, safety and pharmacokinetics of multiple doses in an RSV challenge study, 2018. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03382431?term=PC786&phase=12&draw=2&rank=2. Accessed 20 September 2021.

- DeVincenzo J, Tait D, Oluwayi O, Mori J, Thomas E, Mathews N. Safety and efficacy of oral RV521 in a human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) Phase 2a Challenge study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:A7715.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Safety, pharmacokinetics and antiviral activity of RV521 Against RSV, 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03258502. Accessed 20 September 2021.

- Chemaly RF, Dadwal SS, Bergeron A, Ljungman P, Kim YJ, Cheng GS, et al. A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of presatovir for the treatment of respiratory syncytial virus upper respiratory tract infection in hematopoietic-cell transplant recipients. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020;71(11):2777–86.

- Marty FM, Chemaly RF, Mullane KM, Lee DG, Hirsch HH, Small CB, et al. A phase 2b, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study evaluating antiviral effects, pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of presatovir in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients with respiratory syncytial virus infection of the. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020;71(11):2787–95.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Presatovir in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients with respiratory syncytial virus infection of the upper respiratory tract, 2018. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02254408?term=02254408&draw=2&rank=1. Accessed 20 September 2021.

- Stevens M, Rusch S, DeVincenzo J, Kim YI, Harrison L, Meals EA, et al. Antiviral activity of oral JNJ-53718678 in healthy adult volunteers challenged with respiratory syncytial virus: A placebo-controlled study. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2018;218(5):748–56.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Study to evaluate antiviral activity, safety, and pharmacokinetics of repeated doses of orally administered JNJ 53718678 against respiratory syncytial virus infection, 2019. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02387606?term=NCT02387606&draw=2&rank=1. Accessed 20 September 2021.

of interest

are looking at

saved

next event

This content has been developed independently by Medthority who previously received educational funding in order to help provide its healthcare professional members with access to the highest quality medical and scientific information, education and associated relevant content.