Ovarian cancer

Types and stages of ovarian cancer

Ovarian cancer is the eighth most commonly occurring cancer in women and the 18th most common cancer in the world1

Prevalence, incidence and mortality

In developed countries, ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynaecologic malignancy2,3. It is estimated that in 2020, 6.6 per 100,000 women of any age worldwide had ovarian cancer, and 4.2 per 100,000 women died from ovarian cancer4.

Figure 1 below highlights the incidence and mortality rates of ovarian cancer in the world, relative to other cancers occurring in females.

Figure 1. Estimated age-standardised global incidence and mortality rates in 2020, females, all ages (Adapted4). ASR, age-standardised rate.

Survival rates vary between geographic locations due to a range of factors including:

- background mortality rates

- data collection lag

- access to early diagnosis

- access to optimal treatment5

Early ovarian cancer is difficult to detect. It is often asymptomatic6 or the symptoms are non-specific in the early stages7. Common symptoms include abdominal pain, abdominal bloating or distension, change in bowel habit, fatigue, pelvic pain, weight loss, urinary frequency, abdominal or pelvic mass, loss of appetite, urinary urgency and ascites8.

Common methods of diagnosis include transvaginal ultrasound and the CA-125 blood test, which measures levels of CA-125 protein in the blood. CA-125 can be a useful tumour marker and help guide treatment, however as a screening test its results tend to be most reliable in women aged 50 or over8,9.

Over two-thirds of patients who are initially diagnosed are already at an advanced stage of the disease10 when survival outcomes are worse6. With prognosis being closely related to the stage at diagnosis11,12, this results in a poor prognosis overall. In addition, survival outcomes are worse in the elderly6.

Following standard surgery and chemotherapy, most cancers recur within 12–18 months13. Treatment options include surgery, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies. The utility of these therapies varies by stage.

Ovarian cancer survival

Despite significant improvements in the 5–year survival rate over the past 30 years, the prognosis of ovarian cancer continues to be poor overall14. Ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynaecologic malignancy7, with the 5–year relative survival rate being approximately 49%14.

Figure 2. Spread at diagnosis with associated survival (Adapted5).

Figure 3. Five–year net survival by FIGO stage, including incidence by stage: Women in England diagnosed 2013–2017, followed up to 2018 (Adapted5). FIGO, The International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics.

Unmet needs in ovarian cancer

Given the typically late stage of the disease at first diagnosis and associated poor prognosis, there are a number of unmet needs in ovarian cancer.

- Although earlier diagnosis is needed12, the symptoms of early disease are vague and there is no screening test7, making early diagnosis very difficult

- Over 80% of women with advanced ovarian cancer will experience recurrence, and it is broadly incurable7. With recent regulatory approvals for targeted and antiangiogenic agents to treat both newly diagnosed and recurrent ovarian cancer6,15, new treatment strategies are needed

Types of ovarian cancer

There are over 30 types of ovarian cancers, and they are categorised according to the cell type of origin, being either epithelial, germ, or stromal16.

1. Epithelial ovarian cancer

- The most common type17 of ovarian cancer, representing 90% of malignant tumours6

- More common in women over 50 years of age17

- Full name is ‘epithelial ovarian cancer’ but is often referred to simply as ‘ovarian cancer’17

- Many of this type originate in the fallopian tubes17

- May be divided into subtypes according to appearance under a microscope, however the subtypes are treated in the same way17

- A less common subtype is ‘borderline ovarian cancer’, also known as ‘low malignant potential tumour’. This subtype tends to be confined to the ovary and is more common in young women17

2. Germ cell ovarian cancer

- This type is rare, making up approximately 2% of all ovarian cancers18

- Occur most commonly in teenage girls or young women18

- Less common in women in their 60s18

- Dysgerminomas are the most common tumour type in germ cell ovarian cancer19

3. Stromal cell ovarian cancer

- A rare type of ovarian cancer17

- Often diagnosed earlier than other types18

- The most common subtypes are granulosa-theca tumours and Sertoli-Leydig cell tumours, which are rare18

- Granulosa cell tumour is another subtype, which is also rare18

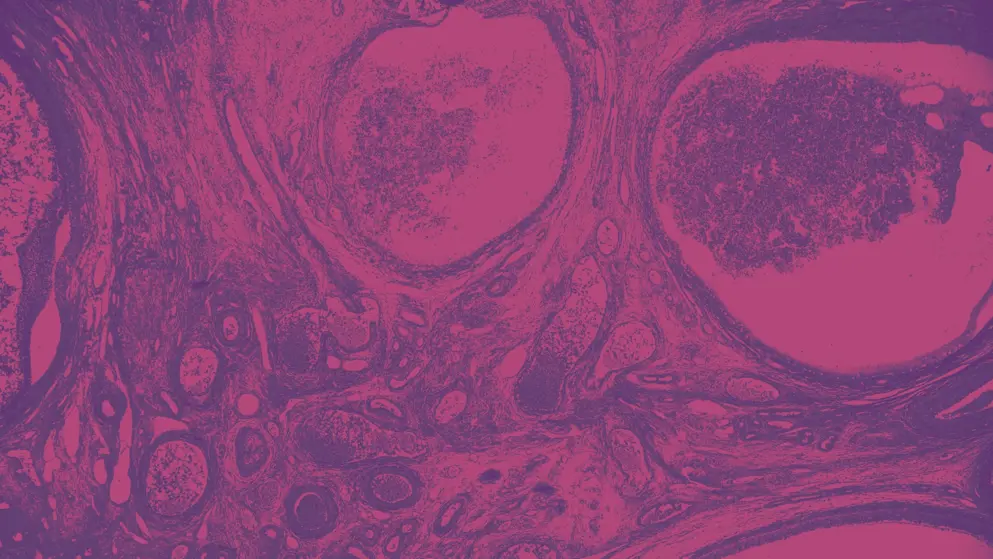

Figure 4. Ovarian cancer types (Adapted20).

Stages

Two systems are used for staging ovarian cancers: The Union for International Cancer Control’s TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours (TNM) system, and the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system6. Both systems provide a means to classify the extent of disease progression and therefore aid clinicians to assess the prognosis and plan treatment21. While computed tomography (CT) scans can help determine the intra-abdominal spread of disease, it is recommended that ovarian cancers are staged surgically22. By determining the histologic diagnosis, the stage and therefore prognosis of the patient can be assessed22.

The TNM system classifies tumours according to the size of the primary tumour (designated ‘T’), the presence (and extent) or absence of regional lymph node metastasis (designated ‘N’), and the presence or absence of distant metastasis (designated ‘M’). The extent of malignancy is designated by the addition of a number to each component21.

The FIGO staging system similarly classifies a cancer according to tumour size and spread. This system comprises four stages, each of which contains several substages. The updated and revised FIGO staging system combines the classifications of ovarian, fallopian tube and peritoneum cancers, and for greater precision it is based on findings ostensibly made through surgical exploration22,23.

Figure 5 indicates the FIGO and equivalent TNM staging classifications for cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube and peritoneum. Note the associated diagrams which illustrate progression of the disease throughout the reproductive system.

Figure 5. Classification of FIGO staging and its equivalent TNM classification for cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube and peritoneum (Adapted22,24). FIGO, The International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics; M, presence or absence of distant metastasis; N, presence (and extent) or absence of regional lymph node metastasis; T, size of primary tumour; TNM, The Union for International Cancer Control’s TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours system.

According to the TNM system of classification, regional lymph nodes (N) and distant metastasis (M) are designated as follows:

- Nx: regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

- N0: no regional lymph node metastasis

- N1: regional lymph node metastasis

- Mx: distant metastasis cannot be assessed

- M0: no distant metastasis

- M1: distant metastasis (excluding peritoneal metastasis)22

Other major recommendations from the FIGO classification system include:

- histologic type (includes grading) to be recorded

- the primary site (ovary, fallopian tube or peritoneum) to be designated if possible

- stage I tumours may be upgraded to stage II if involved with dense adhesions with tumour cells histologically demonstrated in the adhesions25

Take our quiz in the next section to test your knowledge. We recommend you read all the information on this page before taking the quiz.

Treatment options for ovarian cancer

There is no effective screening test for ovarian cancer7. Diagnosis commonly occurs in the late stages of the disease, and recurrence tends to be high7. Standard treatment is surgery followed by combination chemotherapy7. The recent increased incorporation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy has demonstrated some improvement in morbidity and possibly survival25

Enhanced knowledge of ovarian cancer stages and subtypes in recent years has contributed to improvements in both diagnosis and treatment. It is important for healthcare professionals to base therapeutic decisions on both tumour and patient characteristics: with particular attention being paid to the disease stage and molecular features of the cancer subtype6.

Treatment of ovarian cancer includes debulking surgery to remove residual disease when possible, and systemic treatment that is appropriate given the patient characteristics and the cancer subtype, disease stage and biology26. This may include chemotherapy and targeted therapies such as PARP inhibitors and antiangiogenic agents6.

Surgery

The aim of surgery is threefold:

- confirmation of diagnosis

- determination of disease extent

- resection of all visible tumour27,28

Although it is common for ovarian cancer patients to be treated with surgery in the first instance, patients who are not medically fit may instead be treated with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy first and be considered for surgery later 29-33. In patients who are not candidates for optimal debulking, neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking surgery and further chemotherapy is recommended34-36.

The approach to surgery is dependent on whether the tumour is visible outside the ovaries.

Surgical approach according to Cancer Research UK30

In early stage ovarian cancer:

- surgery to remove the cancer, which may include removal of the womb, cervix, ovaries and fallopian tubes (total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy). In some low grade ovarian cancers (stage IA), it may be possible to only remove the affected ovary and fallopian tube, preserving fertility

- surgical staging to determine microscopic metastases

In advanced ovarian cancer (stages II – IV):

- total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

- primary debulking surgery (removal of as much of the cancer as possible)

- interval debulking surgery may be indicated

- may include bowel resection

- surgical staging to determine microscopic metastases

Targeted therapies

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) has approved the PARP inhibitors olaparib37,38, niraparib39,40 and rucaparib42 in the first-line setting for ovarian cancer, as well as bevacizumab, an angiogenesis inhibitor, in first-line and subsequent settings43,44.

PARP inhibitors provide new targeted treatment options for ovarian cancer patients. They work by preventing effective DNA repair, helping trigger cancer cell death45.

Table 1. Approved therapies for ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer (Adapted46,47).

| EMA, European Medicines Agency; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; N, no; Y, yes. | |||

| Therapy type | Generic name | FDA approved | EMA approved |

| Chemotherapies | Melphalan |

Y | Y |

| Carboplatin | Y | Y | |

| Cisplatin | Y | Y | |

| Cyclophosphamide | Y | Y | |

| Doxorubicin | Y | Y | |

| Gemcitabine | Y | Y | |

| Topotecan | Y | Y | |

| Paclitaxel | Y | Y | |

| Thiotepa | Y | Y | |

| Targeted therapies | Bevacizumab | Y | Y |

| Olaparib | Y | Y | |

| Rucaparib | Y | Y | |

| Niraparib | Y | Y | |

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy, or radiotherapy, is not commonly used as a treatment for ovarian cancer due to the toxicity of whole abdominal radiotherapy involved in older techniques, and also due to advances in systemic therapies31.

Radiotherapy can be effective for treating areas in which the cancer has spread, whether close to the main tumour or in a more distant organ32,33. Radiotherapy can also be an effective treatment for women with ovarian clear cell carcinoma, focal metastatic disease, the presence of micrometastatic disease in the peritoneal cavity after surgery, and for palliation of advanced disease31.

Chemotherapies

Chemotherapy is most commonly a systemic treatment. It can be administered as primary treatment, before surgery or after surgery, but is usually administered 2–4 weeks after surgery in order to destroy any remaining cancer cells34. The treatment regimen will depend on the type and stage of ovarian cancer35.

In patients with ovarian cancer at an advanced stage, chemotherapy before surgical intervention may be appropriate, provided there has been cytologic or histologic confirmation of the diagnosis22.

Chemotherapy for epithelial ovarian cancer

The majority of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer require surgery as well as chemotherapy29. Typically, chemotherapy treatment in these patients involves the administration of a combination of two chemotherapy agents: a platinum compound and a taxane35. In patients not treated with chemotherapy, it is important that they are closely and regularly monitored by way of serum CA-125 estimation, clinical examination and ultrasonography if an ovary is present29.

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy may be administered in addition to systemic chemotherapy, in patients with stage III epithelial ovarian cancer whose cancer was optimally debulked35.

Chemotherapy for germ cell tumours

Germ cell malignancies are amongst the most curable cancers, thanks to highly effective platinum-based chemotherapy treatments22. Treatment typically involves combination chemotherapy such as BEP, which includes bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin35. The most common germ cell tumour, dysgerminoma36, can often be treated with a less toxic combination of carboplatin and etoposide35. Other combinations of chemotherapy drugs can be used if the cancer recurs or does not respond to treatment35.

Chemotherapy for stromal cell tumours

Stromal cell tumours are not typically treated with chemotherapeutic agents. When they are, typical treatment is the combination of carboplatin plus paclitaxel or PEB (cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin)35.

Take our quiz and test your knowledge at the end of this page. We recommend you read all the information on this page before taking the quiz.

Treatment sequencing in ovarian cancer

In most stages of ovarian cancer, initial treatment involves surgery in order to remove the tumour, assign the appropriate stage, and to debulk the tumour where possible48. Other treatments such as chemotherapy and targeted therapies may be appropriate following this initial treatment.

Treatment sequencing

Figure 6 outlines the high-level treatment landscape for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer in first-line, first-line maintenance and recurrent disease settings according to approved EMA indications.

Figure 6. High-level treatment landscape in ovarian cancer according to EMA-approved indications37, 49,50. EMA, European Medicines Agency. Refer to EMA label for complete indication descriptions.

BRCA (BReast CAncer) 1 and 2 genes are present in all women and act to supress tumour growth; however, 1 in 500 women have mutations in these genes that will contribute to cancer52

The BRCA genes encode for BRCA proteins, which play a role in repairing DNA via the homologous recombination repair pathway. When the gene is mutated, this leads to homologous recombination deficiency (HRD)53 .

Table 2 below summarises the preferred treatment sequencing approach published by Mirza et al. according to patient subgroup. Note the subgroups are categorised according to BRCA mutation and HRD status51.

Table 2. Treatment approach by patient subgroup (Adapted51).

| BRCA, breast cancer gene; HRD, homologous recombination deficiency; PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase; PDS, primary debulking surgery; PLD, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. | |

| Population | Treatment sequence (front-line → recurrence) |

| Stage III–IV, BRCA mutated | • Olaparib maintenance → chemotherapy + bevacizumab • Platinum + paclitaxel followed by olaparib maintenance → platinum-based chemotherapy + bevacizumab • Olaparib maintenance → carboplatin + PLD + bevacizumab with bevacizumab maintenance • Olaparib or niraparib maintenance (equal preference) → chemotherapy (platinum based or not, depending on the relapse) + bevacizumab • Carboplatin + paclitaxel followed by olaparib with or without bevacizumab → platinum doublet followed by PARP inhibitor if PARP inhibitor naive or did not progress on prior PARP inhibitor • Olaparib + bevacizumab maintenance → chemotherapy • Olaparib maintenance → PLD + carboplatin with rucaparib maintenance |

| Stage III–IV, non-BRCA mutated; HRD unavailable/unvalidated/unknown | • Niraparib maintenance → carboplatin + PLD + bevacizumab with bevacizumab maintenance • Niraparib maintenance → chemotherapy (platinum based or not, depending on the relapse) + bevacizumab • Carboplatin + paclitaxel followed by niraparib → platinum doublet followed by PARP inhibitor if PARP inhibitor naive or platinum doublet + bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab if previously treated with PARP inhibitor • Niraparib maintenance → chemotherapy + bevacizumab • Olaparib + bevacizumab maintenance → chemotherapy • Carboplatin + paclitaxel + bevacizumab with bevacizumab maintenance → carboplatin + paclitaxel + bevacizumab with bevacizumab maintenance • Platinum + paclitaxel + bevacizumab → platinum-based chemotherapy followed by PARP inhibitor |

| Stage III–IV; non-BRCA mutated; HRD positive | • Olaparib + bevacizumab maintenance → chemotherapy • Olaparib + bevacizumab maintenance → chemotherapy + bevacizumab • Platinum + paclitaxel + bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab + olaparib → platinum-based chemotherapy • Carboplatin + paclitaxel + bevacizumab with bevacizumab + olaparib maintenance → carboplatin + PLD with rucaparib maintenance • Niraparib maintenance → carboplatin + PLD + bevacizumab with bevacizumab maintenance • Niraparib maintenance → chemotherapy (platinum based or not depending on the relapse) + bevacizumab • Carboplatin + paclitaxel followed by niraparib → platinum doublet followed by PARP inhibitor if PARP inhibitor naive or platinum doublet + bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab if previously treated with PARP inhibitor |

| Stage III–IV; non-BRCA mutated; HRD negative | • Bevacizumab → chemotherapy followed by PARP inhibitor • Bevacizumab → chemotherapy + PARP inhibitor • Platinum + paclitaxel + bevacizumab → platinum-based chemotherapy followed by PARP inhibitor • Carboplatin + paclitaxel + bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab → platinum doublet + bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab • Paclitaxel + carboplatin + bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab → carboplatin + paclitaxel + bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab |

While all authors in the preferred treatment approach above agree that biomarker status is the primary factor to consider for treatment decisions, some also recognise that additional clinical variables such as disease burden at diagnosis are important factors for consideration.

Figure 7 outlines key considerations when selecting the optimal treatment for women with ovarian cancer, both in the front-line and recurrent settings. It is important to refer to such factors as the patient’s preferences, characteristics of the disease, any existing comorbidities, tumour stage, and drug toxicities54.

Figure 7. Key considerations to help guide optimal treatment decisions for women with newly diagnosed and recurrent advanced epithelial ovarian cancer (Adapted54). BRCA, BReast CAncer gene; HRD, homologous recombination deficiency; HRP, homologous recombination proficiency; IDS, interval debulking surgery; PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase; PDS, primary debulking surgery; PFI, platinum-free interval; RT, residual tumour.

Maintenance

The goal of maintenance treatment is to prevent the growth of cancer cells and prevent recurrence55. However, relapse in women with advanced-stage disease who have completed first-line treatment is high7 in ovarian cancer, at approximately 85%56. Maintenance chemotherapy after first-line therapy is not supported by evidence22.

A meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials that compared PARP inhibitors with placebo in first-line maintenance treatment of ovarian cancer concluded that PARP inhibitors are an effective maintenance therapy in women with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer who had been treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. The significant improvement in progression-free survival was observed in women regardless of BRCA alteration or HRD status57.

Take our quiz and test your knowledge in the next section. We recommend you read all the information on this page before taking the quiz.

First-line maintenance strategies in ovarian cancer

Watch the videos of Professor Ray-Coquard and Dr Mirza to learn about the first-line maintenance strategies currently in use to treat ovarian cancer. Find out how first-line maintenance has changed in recent years and what the current recommended treatments are in this setting.

Up until recently, first-line maintenance strategies for newly diagnosed advanced stage ovarian cancer were limited and provided little benefit, with relapse after initial treatment being very high in the years following. The standard of care has traditionally been surgery plus platinum-based chemotherapy58.

Over the last 10 years, progression-free survival has improved compared to chemotherapy alone, mainly due to the antiangiogenic agent bevacizumab used in the maintenance setting58. More recently, targeted agents are being used to treat newly diagnosed and recurrent ovarian cancer6,15: namely the PARP inhibitors olaparib37, niraparib40, and rucaparib42,44,58.

PARP inhibitors are an exciting recent addition to the suite of treatment options available for ovarian cancer: transforming management of the disease59. However, care must be taken when selecting the appropriate inhibitor for patients.

Learn more about PARP inhibitor selection

Research demonstrates the effectiveness of PARP inhibitors as first-line maintenance therapy in women with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer following platinum-based chemotherapy, particularly in patients with BRCA mutations or other homologous recombination deficiencies57. In terms of efficacy, the hazard ratios demonstrated of niraparib, olaparib and rucaparib are very low, as can be seen in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Approved targeted therapies for ovarian cancer in the front-line setting with reference to key clinical trials data (Adapted54). gBRCA mut, germline BRCA1/2 gene mutation; HR, hazard ratio; HRD, homologous recombination deficient; HRP, homologous recombination proficient; PFS, progression-free survival; sBRCA mut, somatic BRCA1/2 gene mutation; NR, not reached.

While PARP inhibitors have become standard therapy in the maintenance of platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer, there are risks of adverse events to be aware of. In a systematic review and network meta-analysis of phase 2 or 3 randomised controlled trials, there was a statistically significant higher risk of anaemia, dizziness, dyspnoea, fatigue, decreased appetite, nausea, vomiting, and neutropenia in ovarian cancer patients being treated with a PARP inhibitor compared to placebo. Furthermore, in all RCTs analysed, dose reductions due to AEs occurred60.

The approved PARP inhibitors niraparib, olaparib and rucaparib have a similar mode of action, and their differences in efficacy and toxicity may be due to their selectivity: with niraparib being more selective towards PARP1 and PARP2, and olaparib and rucaparib being less selective but more robust inhibitors of PARP1. In addition, binding affinity and pharmacokinetics are different across the three PARP inhibitors: perhaps also accounting for differences in observable efficacy and toxicity60.

The optimal treatment strategy will need to consider a number of factors including identification of the appropriate population for treatment, timing of that treatment, and the characteristics of the patient and disease. Reference to the subgroups analysed in clinical trials may provide some guidance54.

Find out more from ESMO 2022 highlights

Overview of genetic mutations and relevance to ovarian cancer

- BRCA1 and BRCA2 are known as tumour suppressor genes because they produce proteins that help repair DNA that is damaged52

- People who have inherited harmful variants (also known as mutations or alterations) of BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes are at a higher risk of some types of cancer including ovarian and breast cancer52

- Mutations may occur in germinal or somatic tissue. When a mutation is somatic, it will not be passed on to progeny, however mutations that are germinal (germline mutations) can be passed to all or some progeny61

- A person who inherits a harmful variant of BRCA1 or BRCA2 from either parent, is said to have an inherited or germline BRCA1/2 mutation. This mutation is present in one copy of the gene in all cells of the body from birth52

- In a person with a germline BRCA1/2 mutation, the other copy of the BRCA1/2 gene would be normal. However, if that normal copy of the gene is lost or changes in some cells, a somatic alteration has occurred52

- The BRCA gene helps repair DNA via the homologous recombination repair pathway. When the gene is mutated, this leads to homologous recombination deficiency (HRD)53

Learn more about PARP inhibitor mechanism of action

HRD status in the ovarian cancer maintenance setting

In brief, PARP inhibitors work by selectively inducing a process known as ‘synthetic lethality’ in cancer cells that lack the ability to repair double stranded DNA breaks through the homologous recombination repair pathway. Such tumours are said to be ‘homologous recombination deficient’ (HRD). For example, BRCA1/2 genes play a key role in the homologous recombination repair pathway, and cancer cells with BRCA1/2 mutation are considered HR deficient62.

HRD status is an important consideration when selecting the appropriate first-line treatment for women with ovarian cancer, although there are several factors to consider regarding the testing itself, such as the thresholds that indicate positivity, and the potentiality of changes to HRD status occurring over time and in response to platinum chemotherapy51.

To learn about PARP inhibitor mode of action, indications for treatment, and efficacy and safety, progress to the next section of this Learning Zone.

References

- Ovarian cancer statistics | World Cancer Research Fund. https://www.wcrf.org/dietandcancer/cancer-trends/ovarian-cancer-statistics. Accessed 7 April 2021.

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2015 - SEER Statistics. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2015/. Accessed 8 April 2021.

- Zhang Y, Luo G, Li M, Guo P, Xiao Y, Ji H, et al. Global patterns and trends in ovarian cancer incidence: Age, period and birth cohort analysis. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):984.

- Cancer Today. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home. Accessed 8 April 2021.

- The World Ovarian Cancer Coalition Atlas Global Trends In Incidence, Mortality And Survival. 2020 https://worldovariancancercoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/2020-World-Ovarian-Cancer-Atlas_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 8 April 2021.

- Vergote I, Denys H, de Greve J, Gennigens C, van de Vijver K, Kerger J, et al. Treatment algorithm in patients with ovarian cancer. Facts, views & vision in ObGyn. 2020;12(3):227–239.

- Stewart C, Ralyea C, Lockwood S. Ovarian Cancer: An Integrated Review. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2019;35(2):151–156.

- Funston G, Hamilton W, Abel G, Crosbie EJ, Rous B, Walter FM. The diagnostic performance of CA125 for the detection of ovarian and non-ovarian cancer in primary care: A population-based cohort study. PLoS Medicine. 2020;17(10):e1003295.

- American Cancer Society. 2020. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/ovarian-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/detection.html. Accessed 4 June 2021.

- Colombo N, Sessa C, Bois A du, Ledermann J, Querleu D. ESMO–ESGO consensus conference recommendations on ovarian cancer: pathology and molecular biology, early and advanced stages, borderline tumours and recurrent disease. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019;0:14.

- Andrew E Green M. Ovarian Cancer: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/255771-overview. Accessed 8 April 2021.

- Woodward ER, Sleightholme H v., Considine AM, Williamson S, McHugo JM, Cruger DG. Annual surveillance by CA125 and transvaginal ultrasound for ovarian cancer in both high-risk and population risk women is ineffective. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2007;114(12):1500–1509.

- Colombo N, Lorusso D, Scollo P. Impact of recurrence of ovarian cancer on quality of life and outlook for the future. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2017;27(6):1134–1140.

- Ovarian Cancer — Cancer Stat Facts. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ovary.html. Accessed 19 April 2021.

- Lheureux S, Braunstein M, Oza AM. Epithelial ovarian cancer: Evolution of management in the era of precision medicine. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2019. doi:10.3322/caac.21559.

- What Are the Types of Ovarian Tumors? | WebMD. 2021. https://www.webmd.com/ovarian-cancer/guide/types-ovarian-tumors. Accessed 8 April 2021.

- Types of Ovarian Cancer | Cancer Australia. 2020. https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/affected-cancer/cancer-types/ovarian-cancer/types-ovarian-cancer. Accessed 8 April 2021.

- Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment. https://www.webmd.com/ovarian-cancer/guide/ovarian-germ-cell-tumors. Accessed 8 April 2021.

- Chris O’Brien Lifehouse. Ovarian Germ Cell Tumours. https://www.mylifehouse.org.au/departments/gynae-oncology/clinical-practice-guidelines-ovarian-germ-cell-tumours/. Accessed 12 April 2021.

- Ptak A, Hoffmann M, Rak A. The Ovary as a Target Organ for Bisphenol A Toxicity. In: Bisphenol A Exposure and Health Risks. 2017. InTech doi:10.5772/intechopen.68241.

- TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours - Google Books. https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=642GDQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP12&ots=dAJYSJJIkj&sig=Oe-9znuA2e5-McpEWv12zpwEcLo&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false. Accessed 13 April 2021.

- Berek JS, Kehoe ST, Kumar L, Friedlander M. Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2018;143:59–78.

- Staging for OVFTP malignancies | Figo. https://www.figo.org/news/staging-ovftp-malignancies. Accessed 13 April 2021.

- Ovarian Epithelial, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version - National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/ovarian/hp/ovarian-epithelial-treatment-pdq. Accessed 15 April 2021.

- Andrew E Green M. Ovarian Cancer Workup: Approach Considerations, Screening, Tumor Markers. 2020. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/255771-workup#c7. Accessed 7 April 2021.

- Lheureux S, Braunstein M, Oza AM. Epithelial ovarian cancer: Evolution of management in the era of precision medicine. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2019;69(4). doi:10.3322/caac.21559.

- American Cancer Society. 2018. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/ovarian-cancer/treating/surgery.html. Accessed 21 June 2021.

- Ovarian Cancer Signs & Symptoms | OCRA. https://ocrahope.org/patients/about-ovarian-cancer/. Accessed 21 June 2021.

- Ovarian Cancer Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Choosing Appropriate Surgery, Surgical Staging. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/255771-treatment. Accessed 7 April 2021.

- Types of surgery | Ovarian cancer | Cancer Research UK. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/ovarian-cancer/treatment/surgery/types-surgery. Accessed 5 July 2021.

- Fields EC, McGuire WP, Lin L, Temkin SM. Radiation treatment in women with ovarian cancer: Past, present, and future. Frontiers in Oncology. 2017;7(AUG):177.

- Cancer Research UK. Having Radiotherapy for Ovarian Cancer. 2019. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/ovarian-cancer/treatment/radiotherapy/having-treatment. Accessed 9 April 2021.

- Cancer Council NSW. Radiation Therapy for Ovarian Cancer. https://www.cancercouncil.com.au/ovarian-cancer/treatment/radiotherapy/. Accessed 9 April 2021.

- Chemotherapy for Ovarian Cancer | Cancer Council NSW. https://www.cancercouncil.com.au/ovarian-cancer/treatment/chemotherapy/. Accessed 9 April 2021.

- American Cancer Society. Chemotherapy for Ovarian Cancer. 2018. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/ovarian-cancer/treating/chemotherapy.html. Accessed 9 April 2021.

- Ovarian Germ Cell Tumor (Dysgerminoma). https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/6186-ovarian-germ-cell-tumors. Accessed 9 April 2021.

- European Medicines Agency. Annex I Summary of Product Characteristics | Lynparza. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/lynparza-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 9 April 2021.

- Food and Drug Administration. Highlights of Prescribing Information | Lynparza. https://den8dhaj6zs0e.cloudfront.net/50fd68b9-106b-4550-b5d0-12b045f8b184/00997c3f-5912-486f-a7db-930b4639cd51/00997c3f-5912-486f-a7db-930b4639cd51_viewable_rendition__v.pdf. Accessed 6 Oct 22.

- Food and Drug Administration. Highlights of Prescribing Information | Zejula. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/208447s015s017lbledt.pdf. Accessed 12 April 2021.

- European Medicines Agency. Zejula. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/zejula. Accessed 8 April 2021.

- Food and Drug Administration. Highlights of Prescribing Information | Rubraca. https://clovisoncology.com/pdfs/RubracaUSPI.pdf. Accessed 6 Oct 2022.Accessed 6 Oct 22.

- European Medicines Agency. Annex I Summary of Product Characteristics | Rubraca. 2020. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/rubraca-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 9 April 2021.

- Food And Drug Administration. HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION | Avastin. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/125085s323lbl.pdf. Accessed 22 April 2021.

- European Medicines Agency. Annex I Summary of Product Characteristics | Avastin. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/avastin-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 9 April 2021.

- Gourley C, Balmaña J, Ledermann JA, Serra V, Dent R, Loibl S, et al. Moving from poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition to targeting DNA repair and DNA damage response in cancer therapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2019;37(25):2257–2269.

- National Cancer Institute. Drugs Approved for Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, or Primary Peritoneal Cancer. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/drugs/ovarian. Accessed 13 April 2021.

- European Medicines Agency. Annex I Summary of Product Characteristics | Doxolipad. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/doxolipad. Accessed 13 April 2021.

- Treatment of Invasive Epithelial Ovarian Cancers, by Stage. 2020. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/ovarian-cancer/treating/by-stage.html. Accessed 9 April 2021.

- European Medicines Agency. Annex I Summary of Product Characteristics | Rubraca. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/rubraca-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 9 April 2021.

- European Medicines Agency. Annex I Summary of Product Characteristics | Zejula. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/zejula-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 9 April 2021.

- Mirza MR, Coleman RL, González-Martín A, Moore KN, Colombo N, Ray-Coquard I, et al. The forefront of ovarian cancer therapy: update on PARP inhibitors. Annals of Oncology. 2020;31(9):1148–1159.

- BRCA Gene Mutations: Cancer Risk and Genetic Testing Fact Sheet - National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/genetics/brca-fact-sheet#what-are-brca1-and-brca2. Accessed 6 May 2021.

- da Cunha Colombo Bonadio RR, Fogace RN, Miranda VC, Diz MDPE. Homologous recombination deficiency in ovarian cancer: A review of its epidemiology and management. Clinics. 2018;73(Suppl 1). doi:10.6061/clinics/2018/e450s.

- Nero C, Ciccarone F, Pietragalla A, Duranti S, Daniele G, Salutari V, et al. Ovarian cancer treatments strategy: Focus on parp inhibitors and immune check point inhibitors. Cancers. 2021;13(6):1–13.

- Khalique S, Hook JM, Ledermann JA. Maintenance therapy in ovarian cancer. Current Opinion in Oncology. 2014;26(5):521–528.

- González-Martín A, Pothuri B, Vergote I, DePont Christensen R, Graybill W, Mirza MR, et al. Niraparib in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;381(25):2391–2402.

- Lin Q, Liu W, Xu S, Shang H, Li J, Guo Y, et al. PARP inhibitors as maintenance therapy in newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2021;128(3):485–493.

- Reverdy T, Sajous C, Péron J, Glehen O, Bakrin N, Gertych W, et al. Front-line maintenance therapy in advanced ovarian cancer—current advances and perspectives. Cancers. 2020;12(9):1–18.

- Veneris JT, Matulonis UA, Liu JF, Konstantinopoulos PA. Choosing wisely: Selecting PARP inhibitor combinations to promote anti-tumor immune responses beyond BRCA mutations. Gynecologic Oncology. 2020;156(2):488–497.

- Stemmer A, Shafran I, Stemmer SM, Tsoref D. Comparison of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors (parpis) as maintenance therapy for platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cancers. 2020;12(10):1–12.

- Griffiths AJ, Miller JH, Suzuki DT, Lewontin RC, Gelbart WM. Somatic versus germinal mutation. 2000. W. H. Freeman https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK21894/. Accessed 6 May 2021.

- Kim DS, Camacho C v., Kraus WL. Alternate therapeutic pathways for PARP inhibitors and potential mechanisms of resistance. Experimental and Molecular Medicine. 2021;53(1):42–51.

of interest

are looking at

saved

next event

This content has been developed independently by Medthority who previously received educational funding in order to help provide its healthcare professional members with access to the highest quality medical and scientific information, education and associated relevant content.