Migraine overview

In this video, two patients with migraine describe the emotional impact of migraine on their mental health and sense of wellbeing. Caitlin expresses the “horror” of photophobia and vertigo, and how migraine has affected her sense of independence. Helen explains the negative effect of migraine on her family, and the deep fear of not knowing when the next migraine attack will occur.

A brief overview of migraine

Migraine is a disabling primary headache disorder, which affects over one billion people worldwide1

Migraine has a female-to-male ratio of 3:11.

Broadly, migraine manifests as recurrent episodes (“attacks”) of headache of moderate-to-severe pain intensity, with a duration between 4–72 hours2. Common symptoms of migraine are nausea, vomiting, photophobia and phonophobia2. Some episodes of migraine are preceded by an aura, characterised by reversible focal neurologic symptoms, commonly involving visual or hemisensory disturbances2.

Best practice migraine diagnosis follows clinical criteria stated in the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3)2. An episode of head pain that is unilateral, pulsating, or worsened by physical activity should prompt a diagnosis of migraine2.

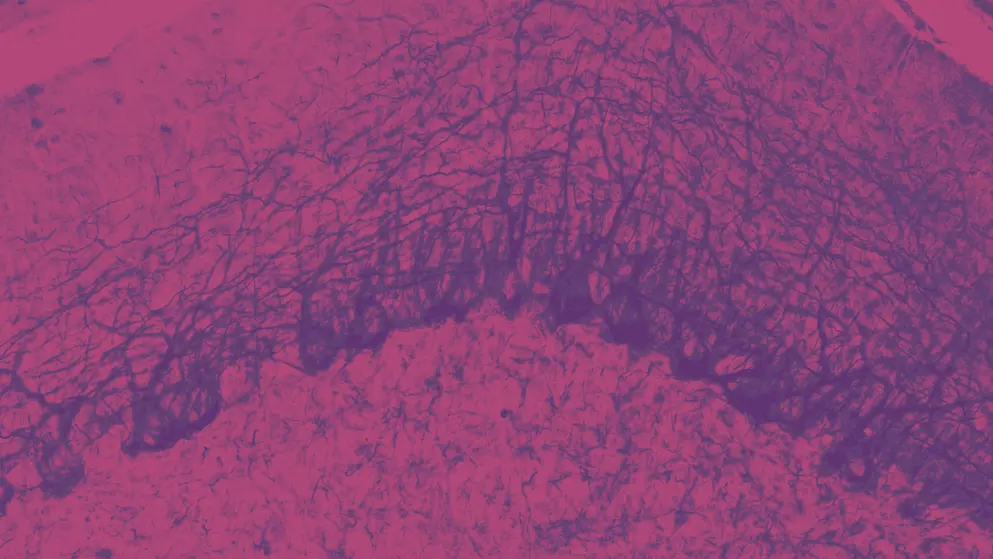

Accumulating evidence indicates that migraine pathogenesis recruits the trigeminal nerve and its axonal projections to the intracranial vasculature3. Nociceptive signals from the trigeminovascular system transmit to brain regions that are hypothesised to be responsible for the experience of migraine pain3.

Progress in explaining migraine has identified signalling molecules that are involved in pathogenesis of a migraine episode3. This knowledge has stimulated development of mechanism-based therapies for migraine, such as therapies based on calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) or pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP)3.

The following sections of this Learning Zone elaborate on these aspects of migraine.

Burden of migraine

According to Professor Zaza Katsarava (Department of Neurology, Evangelical Hospital, Germany), people with migraine “usually go to work because they want to avoid being stigmatised, but they are not really productive.” Watch Professor Katsarava’s interview to learn more about the burden of migraine.

Overall disease burden is evaluated using the disability-adjusted life year (DALY)4. DALY measures years of life lost due to premature mortality (YLL) and years of life lost due to time lived in states of suboptimal health, or years of healthy life lost due to disability (YLD)4. One DALY indicates the loss of 1 year of optimal health4.

In the 2016 Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD), migraine was the second most prevalent global neurological disorder in disability-adjusted life-years (DALY) after stroke (Figure 1)5. In Australasia and western Europe, migraine ranked first for DALY5.

Figure 1. Ranking of age-standardised DALY rates for neurological disorders by selected global regions, 2016 (Adapted5). Adapted with permission according to Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. CNS, central nervous system; DALY, disability-adjusted life-year.

Migraine and dementias, such as Alzheimer’s disease, ranked in the top four contributing neurological conditions in all 21 world regions evaluated in the 2016 GBD5.

In GBD 2019, migraine was second overall in global disability for both sexes and all ages (YLD 4.9, Uncertainty Interval (UI) 0.8–10.1), following low-back pain (YLD 7.4, UI 6.2–8.7), but ranked first in young women for global lost health life (DALY 4.9, UI 0.7–10.6), consistent with the GBD 20166.

No other disease is responsible for more years of lost healthy life in young women than migraine6

Disability burden maintains the high ranking of migraine among the causes of YLDs (and DALYs) in less affluent countries, where shorter life expectancies increase the population proportions of young adults6.

Although there are limitations in the GBD data for migraine burden, including the absence of high-quality epidemiological data from many parts of the world, migraine poses a significant global public health challenge for both sexes and all ages in many countries of the world. Migraine therefore needs greater attention in health policy discussions and research resource allocation1.

Unmet medical needs associated with migraine

According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), an unmet medical need is a condition whose treatment or diagnosis is not sufficiently addressed by current therapy, and requires an immediate need for a defined population, or a longer-term need for society7.

Increased direct and indirect costs associated with migraine

In a retrospective, observational study examining data from the 2016 US National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS), patients with ≥4 monthly migraine days treated with a range of acute prescription or over-the-counter (OTC) and preventive medications self-reported significantly reduced work productivity and increased all-cause healthcare resource use and cost compared with patients without migraine8.

The approval of preventive treatments for migraine, monoclonal antibodies that antagonise CGRP or its receptor, could help meet this unmet need, together with prudent use of other modalities, such as biobehavioural therapies or neurostimulation for prevention8-12

Minimally appropriate care for migraine

The American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study (AMPP) study showed that ~44% of people with migraine never received a medical diagnosis13. Despite receiving a diagnosis of migraine, many diagnosed patients have difficulty accessing acute or preventive treatment for the disease14. An exploratory analysis from AMPP found that only 26% of the original episodic migraine cohort successfully met the three barriers (consultation, diagnosis, treatment) for minimally appropriate care for migraine14.

In the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes Study (CaMEO), <5% of patients with chronic migraine met the three barriers for minimally appropriate care for migraine, and experienced particular adversity in seeking a consultation and receiving a diagnosis of chronic migraine15. In patients who successfully consulted a healthcare professional (HCP) and were diagnosed with migraine, less than half received preventive and acute treatment15. The 2018 Migraine in America Symptoms and Treatment (MAST) Study confirmed that migraine is underdiagnosed and undertreated16.

Overuse of medications for migraine

Treatment guidelines stipulate who should be admitted as an inpatient or outpatient when treating medication overuse in the migraine setting, but clinicians should consult the guidelines in the country in which they practice. In the video below, Professor Katsarava outlines the recommendations in Germany.

In the AMPP study, 49% of patients exclusively used OTC medications for acute treatment of migraine; 29% occasionally used OTC medications or prescription medications13.

Patients with migraine who overuse acute medications can develop medication overuse headache (MOH), which occurs ≥15 days per month in patients with underlying headache disorders, such as migraine2.

In 2017, the FDA issued a warning on all OTC migraine and headache medications17.

HCPs should convey label warnings to patients when recommending acute OTC treatments for migraine and advise against overuse of prescribed acute medications18,19

Informing patients about label warnings is relevant for clinical prescription of opioid analgesics for migraine, given the preponderance of opioid use relative to triptans for migraine, and use of opioids for migraine in hospital emergency rooms18,19.

The remedy for MOH is abrupt withdrawal of the overused medication20, excluding opioid analgesics21. Withdrawal for MOH can be supervised in primary care unless opioids, or other potential addictive drugs, are involved22.

It is not always straightforward for patients to receive a diagnosis of migraine and be perceived as credible by healthcare professionals. In this video, two women living with migraine describe the migraine diagnostic process as endlessly moving “back and forth, because no one knew” and report feeling hopeless when told by clinicians that “you just have migraine”.

In this video, two patients with migraine recount the symptoms and pain of their first migraine attack, and how they coped with it. They describe being “overtaken” by the symptoms, such as photophobia or nausea, and feeling helpless in the face of pain, which was “dreadful”.

Diagnosis of migraine

There are multiple barriers preventing timely diagnosis of migraine. One barrier, noted by Professor Zaza Katsarava (Department of Neurology, Evangelical Hospital, Germany), is that patients often do not know that effective treatments for migraine are available, and may not seek medical advice.

Despite the availability of comprehensive diagnostic criteria for migraine, migraine is often misdiagnosed, and under-treatment of the disease remains a public health challenge2,23,24. A comprehensive approach can promote accurate diagnosis and evidence-based management of migraine2.

Every patient should be given a full explanation of migraine as a disease and of the principles of its diagnosis and management25

Migraine diagnosis tends to be confirmed following a full medical history. With the use of validated diagnostic aids, described below, a comprehensive history allows application of the diagnostic criteria described in the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3)2. Additional investigations beyond physical examination, such as neuroimaging, can be used to confirm or reject suspicions of secondary causes for headache (Table 1)2. ICHD-3 diagnostic criteria for primary headache disorders are summarised in Table 12.

Table 1. ICHD-3 diagnostic criteria for primary headache disorders (Adapted2,25). Adapted with permission according to Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. ICHD-3, International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition.

| ICHD-3 diagnostic criteria for primary headache disorders |

| Migraine without aura |

| 1. At least five attacks that fulfil criteria 2–5 |

| 2. Headache attacks that last 4–72 h when untreated or unsuccessfully treated |

| 3. Headache has at least two of the following four characteristics: • unilateral location • pulsating quality • moderate or severe pain intensity • aggravation by, or causing avoidance of, routine physical activity (for example, walking or climbing stairs) |

| 4. At least one of the following during the headache: • nausea and/or vomiting • photophobia and phonophobia |

| 5. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis |

| Migraine with aura |

| 1. At least two attacks that fulfil criteria 2 and 3 |

| 2. One or more of the following fully reversible aura symptoms: • visual • sensory • speech and/or language • motor • brainstem • retinal |

| 3. At least three of the following six characteristics: • at least one aura symptom spreads gradually over ≥5 min • two or more aura symptoms occur in succession • each individual aura symptom lasts 5–60 min • at least one aura symptom is unilateral • at least one aura symptom is positive • the aura is accompanied with or followed by headache within 60 min |

| 4. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis |

| Chronic migraine |

| 1. Headache (migraine-like or tension-type-like) on ≥15 days/month for >3 months that fulfil criteria 2 and 3 |

| 2. Attacks occur in an individual who has had at least five attacks that fulfil the criteria for migraine without aura and/or for migraine with aura |

| 3. On ≥8 days/month for >3 months, any of the following criteria are met: • criteria 3 and 4 for migraine without aura • criteria 2 and 3 for migraine with aura • believed by the patient to be migraine at onset and relieved by a triptan or ergot derivative |

| 4. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis |

| Medication-overuse headache |

| 1. Headache on ≥15 days/month in an individual with a pre-existing headache disorder |

| 2. Regular overuse for >3 months of one or more drugs that can be taken for acute and/or symptomatic treatment of headache (regular intake of one or more non-opioid analgesics on ≥15 days/month for ≥3 months or any other acute medication or combination of medications on ≥10 days/month for ≥3 months) |

| 3. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis |

Medical history for migraine

A medical history for migraine diagnosis must include at least the following items for the application of ICHD-3 criteria25:

- Accompanying symptoms (e.g., vomiting, nausea, photophobia, phonophobia)

- Age at onset of headache

- Aura symptoms

- Duration and frequency of headache episodes

- History of acute and preventive medication use

- Pain characteristics (e.g., quality, location, intensity, aggravating or relieving factors)

Diagnostic aids for migraine

Migraine diaries

Daily diary entries, recorded by the patient, provide information for the patient and healthcare professional (HCP) on the duration and frequency of headache episodes, accompanying symptoms and use (or misuse) of acute medications25. At follow-up, HCPs can use headache diaries for re-assessing the diagnosis, as needed25.

Digital diaries can bridge the gap between accurate diagnosis and increasing headache burden. Daily monitoring of headache incidence and associated symptoms using an electronic diary can reduce diagnostic errors due to recall bias26,27.

Headache calendars

Patients with migraine can use a calendar to record the temporal patterns of migraine (frequency of migraine, frequency and intensity of headaches) and migraine-associated events, such as menstruation, or acute and preventive medication use25.

Screening tools for migraine

Diagnosis of migraine can be aided by screening instruments that assess if the presented clinical characteristics of headache indicate migraine25. Validated screening instruments include the ID-Migraine questionnaire and the Migraine Screen-Q instrument28,29:

- The ID-Migraine questionnaire has a sensitivity of 0.81, a specificity of 0.75 and a positive predictive value of 0.93 compared with ICHD-3-based diagnosis by a headache specialist28

- The Migraine Screen-Q instrument has a sensitivity of 0.93, a specificity of 0.81 and a positive predictive value of 0.8329

Following use of these instruments, diagnosis can be confirmed by a careful review of the patient’s medical history and/or use of a headache diary or calendar25.

Differential diagnoses for migraine

Differential diagnoses for migraine include other primary headache disorders (Table 2) and some secondary headache disorders (Table 3)25,30.

Table 2. Characteristics of primary headache disorders (Adapted30). Adapted with permission according to Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

| Headache disorder | Headache duration | Headache location | Pain intensity and qualities | Symptoms |

| Migraine | 4–72 h | Usually unilateral | Moderate or severe Pulsating |

Photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, vomiting |

| Tension-type headache | Hours to days or unremitting | Usually bilateral or circumferential | Mild or moderate Pressing or tightening |

Sometimes photophobia or phonophobia (but not both); sometimes mild nausea in chronic tension-type headache |

| Cluster headache | 15–180 min | Strictly unilateral and orbital, supraorbital, and/or temporal | Severe or very severe Overwhelming |

Ipsilateral to the headache: cranial autonomic symptoms, such as conjunctival injection, lacrimation, and nasal congestion |

Table 3. Red flags associated with secondary headaches (Adapted30). Adapted with permission according to Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

| When to look | Red flag | Indication |

| Patient history | Thunderclap headache | Subarachnoid haemorrhage |

| Atypical aura | Transient ischaemic attack, stroke, epilepsy, arteriovenous malformations | |

| Head trauma | Subdural haematoma | |

| Progressive headache | Intracranial space-occupying lesion | |

| Headache aggravated by postures or manoeuvres that raise intracranial pressure | Intracranial hypertension or hypotension | |

| Headache brought on by sneezing, coughing or exercise | Intracranial space-occupying lesion | |

| Headache associated with weight loss and/or change in memory or personality | Suggests secondary headache | |

| Headache onset at >50 years of age | Suggests secondary headache; consider temporal arteritis | |

| Physical examination | Unexplained fever | Meningitis |

| Neck stiffness | Meningitis, subarachnoid haemorrhage | |

| Focal neurological symptoms | Suggests secondary headache | |

| Weight loss | Suggests secondary headache | |

| Impaired memory and/or altered consciousness or personality | Suggests secondary headache |

Differentiation from other primary headache disorders is needed for migraine management; differentiation from secondary headache disorders is necessary because some secondary disorders are potentially life-threatening25,30

Tension-type headache (TTH)

TTH involves bilateral, mild to moderate pain, with a pressing or tightening quality that is not worsened by regular physical activity or exercise (Table 2)2.

Cluster headache

Cluster headaches feature frequently recurrent episodes of unilateral severe or very severe pain intensity, ranging from 15–180 minutes in duration2.

Head pain in cluster headache is accompanied by ipsilateral cranial autonomic symptoms (e.g., nasal congestion, lacrimation, conjunctival injection) (Table 2)2.

Medication-overuse headache (MOH)

MOH is a secondary headache disorder that is a differential diagnosis for chronic migraine21.

Other secondary headache disorders

Some secondary headache disorders present with characteristics that indicate migraine, but specific red flags in the medical history or physical examination should create suspicion (Table 3)30. Red flags indicate the need for further evaluation, such as neuroimaging or lumbar puncture31.

In summary, the main steps of migraine diagnosis require25:

- A careful medical history, allowing application of the ICHD-3 criteria

- Use of validated diagnostic aids and screening tools

- Differential diagnoses

According to Professor Zaza Katsarava (Department of Neurology, Evangelical Hospital, Germany), “…we have different patients with different needs, and we have to adapt the treatment... it is not appropriate to talk about the clear [treatment] sequence. This sequence differs in different countries.” Learn more in the video below about treatment sequencing for migraine.

Standard-of-care acute treatments for migraine

Acute medications should be used early in the headache phase of a migraine attack, as effectiveness relies on timely intervention with the appropriate dose25

Acute treatments for migraine are categorised as first-line, second-line, third-line or adjunct25.

First-line acute medications

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) (acetylsalicylic acid, ibuprofen, diclofenac potassium) are advised25

Second-line acute medications

- Triptans are recommended25

Third-line acute medications

- Ditans and gepants can be considered25

Adjunct acute medications

- Prokinetic antiemetics (domperidone, metoclopramide) can be offered to patients as adjuncts for nausea and/or vomiting25

- Neuromodulatory devices, biobehavioural therapy or acupuncture when medication is contraindicated25

Medications to avoid

- Oral ergot alkaloids, opioid analgesics or barbiturates25

Acute treatments for migraine are summarised in Table 425.

Table 4. Acute treatments for migraine (Adapted25). Adapted with permission according to Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

| Drug class | Drug | Dosage and route | Contraindications |

| First-line medication | |||

| NSAIDs | Acetylsalicylic acid | 900–1,000 mg oral | Gastrointestinal bleeding, heart failure |

| Ibuprofen | 400–600 mg oral | ||

| Diclofenac potassium | 50 mg oral (soluble) | ||

| Other simple analgesics (if NSAIDs are contraindicated) |

Paracetamol | 1,000 mg oral | Hepatic disease, renal failure |

| Antiemetics (when necessary) |

Domperidone | 10 mg oral or suppository | Gastrointestinal bleeding, epilepsy, renal failure, cardiac arrhythmia |

| Metoclopramide | 10 mg oral | Parkinson disease, epilepsy, mechanical ileus |

|

| Second-line medication | |||

| Triptans | Sumatriptan | 50 or 100 mg oral or 6 mg subcutaneous or 10 or 20 mg intranasal | Cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, uncontrolled hypertension, hemiplegic migraine, migraine with brainstem aura |

| Zolmitriptan | 2.5 or 5 mg oral or 5 mg intranasal | ||

| Almotriptan | 12.5 mg oral | ||

| Eletriptan | 20, 40 or 80 mg oral | ||

| Frovatriptan | 2.5 mg oral | ||

| Naratriptan | 2.5 mg oral | ||

| Rizatriptan | 10 mg oral tablet (5 mg if treated with propranolol) or 10 mg mouth-dispersible wafers |

||

| Third-line medication | |||

| Gepants | Ubrogepant | 50, 100 mg oral | Co-administration with strong CYP3A4 inhibitors |

| Rimegepant | 75 mg oral | Hypersensitivity, hepatic impairment | |

| Ditans | Lasmiditan | 50, 100 or 200 mg oral | Pregnancy, concomitant use with drugs that are P-glycoprotein substrates |

Acute treatments for migraine should be used in a stepped-care approach for optimal individualised therapy (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Stepped-care approach for acute treatments for migraine (Adapted25). Adapted with permission according to Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. NSAID, non- steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Frequent, repeated use of acute medication for migraine risks medication-overuse headache (MOH)25

Preventive standard-of-care treatments for migraine

Preventive treatment is an option for patients with migraine who are adversely affected by migraine on ≥2 days per month, despite optimised acute treatment30.

Preventive treatments for migraine, like acute treatments, are classified as first-line, second-line, third-line, or adjunct25. Treatment selection and treatment order follows local clinical practice guidelines and local availability, costs and reimbursement policies25.

First-line preventive medications

- Beta blockers (atenolol, bisoprolol, metoprolol, propranolol), candesartan or topiramate are advised25

Second-line preventive medications

- Amitriptyline, flunarizine or (in men) sodium valproate are recommended25

Third-line preventive medications

- Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies can be considered, including eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab and galcanezumab25

- These medications are approved for the preventive treatment of migraine9-12

- CGRP antibodies could be an option for patients who have contraindications to other preventive treatments due to comorbidities or side effects, or in patients who have poor adherence to treatments where strategies to improve adherence were ineffective32

Adjunct preventive treatments

Acupuncture, biobehavioural therapy or neuromodulatory devices when medication is contraindicated25.

Preventive treatments for migraine are shown in Table 525.

Table 5. Preventive migraine treatments (Adapted25). Adapted with permission according to Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. *Sodium valproate is absolutely contraindicated in women of childbearing potential.

| Drug class | Drug | Dosage and route | Contraindications |

| First-line medication | |||

| Beta blockers | Atenolol | 25–100 mg oral twice daily | Asthma, cardiac failure, Raynaud disease, atrioventricular block, depression |

| Bisoprolol | 5–10 mg oral once daily | ||

| Metoprolol | 50–100 mg oral twice daily or 200 mg modified-release oral once daily |

||

| Propranolol | 80–160 mg oral once or twice daily in long-acting formulations |

||

| Angiotensin II receptor blocker |

Candesartan | 16–32 mg oral per day | Co-administration of aliskiren |

| Anticonvulsant | Topiramate | 50–100 mg oral daily | Nephrolithiasis, pregnancy, lactation, glaucoma |

| Second-line medication | |||

| Tricyclic antidepressant | Amitriptyline | 10–100 mg oral at night | Age <6 years, heart failure, co-administration with monoamine oxidase inhibitors and SSRIs, glaucoma |

| Calcium antagonist | Flunarizine | 5–10 mg oral once daily | Parkinsonism, depression |

| Anticonvulsant | Sodium valproate* | 600–1,500 mg oral once daily | Liver disease, thrombocytopenia, female and of childbearing potential |

| Third-line medication | |||

| Botulinum toxin | OnabotulinumtoxinA | 155–195 units to 31–39 sites every 12 weeks |

Infection at injection site |

| Calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibodies |

Erenumab | 70 or 140 mg subcutaneous once monthly |

Hypersensitivity Not recommended in patients with a history of stroke, subarachnoid haemorrhage, coronary heart disease, inflammatory bowel disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or impaired wound healing |

| Fremanezumab | 225 mg subcutaneous once monthly or 675 mg subcutaneous once quarterly |

||

| Galcanezumab | 240 mg subcutaneous, then 120 mg subcutaneous once monthly |

||

| Eptinezumab | 100 or 300 mg intravenous quarterly |

||

Patients should be encouraged not to abandon preventive treatment in the early stages, as several weeks or months are needed to judge the efficacy of these medications for migraine30

Acute management of migraine should be offered to patients early in the headache phase of the episode25. Preventive treatment should be considered for patients with migraine who experience migraine on ≥2 days per month, despite optimised acute treatment30. Like acute medications, preventive treatments for migraine, are categorised as first-line, second-line, third-line, or adjunct25.

References

- Stovner LJ, Nichols E, Steiner TJ, Abd-Allah F, Abdelalim A, Al-Raddadi RM, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):954–976.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalal. 2018;38:1–211.

- Ashina M, Hansen JM, Do TP, Melo-Carrillo A, Burstein R, Moskowitz MA. Migraine and the trigeminovascular system—40 years and counting. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(8):795–804.

- World Health Organization. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/158. Accessed March 27, 2023.

- Feigin VL, Nichols E, Alam T, Bannick MS, Beghi E, Blake N, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2019;18:459–480.

- Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Jensen R, Uluduz D, Katsarava Z. Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1).

- Guidance for Industry Expedited Programs for Serious Conditions – Drugs and Biologics 2017. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Expedited-Programs-for-Serious-Conditions-Drugs-and-Biologics.pdf.

- Buse DC, Yugrakh MS, Lee LK, Bell J, Cohen JM, Lipton RB. Burden of Illness Among People with Migraine and ≥ 4 Monthly Headache Days While Using Acute and/or Preventive Prescription Medications for Migraine. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(10):1334–1343.

- Aimovig® Highlights of Prescribing Information. 2021. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/761077s009lbl.pdf.

- Emgality® Highights of Prescribing information. 2018. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761063s000lbl.pdf.

- Ajovy® Highlights of Prescribing Information. 2018. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761089s000lbl.pdf.

- Vyepti® Highlights of Prescribing Information. 2020. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/761119s000lbl.pdf.

- Diamond S, Bigal ME, Silberstein S, Loder E, Reed M, Lipton RB. Patterns of Diagnosis and Acute and Preventive Treatment for Migraine in the United States: Results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study. Headache: J Head Face Pain. 2006;47(0):355–363.

- Lipton RB, Serrano D, Holland S, Fanning KM, Reed ML, Buse DC. Barriers to the diagnosis and treatment of migraine: effects of sex, income, and headache features. Headache: J Head Face Pain. 2013;53(1):81–92.

- Dodick DW, Loder EW, Manack Adams A, Buse DC, Fanning KM, Reed ML, et al. Assessing Barriers to Chronic Migraine Consultation, Diagnosis, and Treatment: Results From the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study. Headache: J Head Face Pain. 2016;56(5):821–834.

- Lipton RB, Munjal S, Alam A, Buse DC, Fanning KM, Reed ML, et al. Migraine in America Symptoms and Treatment (MAST) study: baseline study methods, treatment patterns, and gender differences. Headache: J Head Face Pain. 2018;58(9):1408–1426.

- Treating Migraines: More Ways to Fight the Pain. 2017. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/treating-migraines-more-ways-fight-pain. Accessed March 16, 2022.

- 61st Annual Scientific Meeting American Headache Society® July 11-14 2019. Headache: J Head Face Pain. 2019;59:1–208.

- Connelly M, Glynn EF, Hoffman MA, Bickel J. Rates and predictors of using opioids in the emergency department to treat migraine in adolescents and young adults. Ped Emerg Care. 2021;37(12):e981–987.

- Diener HC, Antonaci F, Braschinsky M, Evers S, Jensen R, Lainez M, et al. European Academy of Neurology guideline on the management of medication‐overuse headache. Euro J Neurol. 2020;27(7):1102–1116.

- Diener HC, Dodick D, Evers S, Holle D, Jensen RH, Lipton RB, et al. Pathophysiology, prevention, and treatment of medication overuse headache. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(9):891–902.

- Kristoffersen ES, Straand J, Vetvik KG, Benth JŠ, Russell MB, Lundqvist C. Brief intervention for medication-overuse headache in primary care. The BIMOH study: a double-blind pragmatic cluster randomised parallel controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 2015;86(5):505–512.

- Katsarava Z, Mania M, Lampl C, Herberhold J, Steiner TJ. Poor medical care for people with migraine in Europe – evidence from the Eurolight study. J Headache Pain. 2018;19(1).

- Ashina M, Katsarava Z, Do TP, Buse DC, Pozo-Rosich P, Özge A, et al. Migraine: epidemiology and systems of care. 2021;397(10283):1485–1495.

- Eigenbrodt AK, Ashina H, Khan S, Diener HC, Mitsikostas DD, Sinclair AJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of migraine in ten steps. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(8):501–514.

- Bandarian-Balooch S, Martin PR, McNally B, Brunelli A, Mackenzie S. Electronic-Diary for Recording Headaches, Triggers, and Medication Use: Development and Evaluation. Headache: J Head Face Pain. 2017;57(10):1551–1569.

- Park JW, Chu MK, Kim JM, Park SG, Cho SJ. Analysis of Trigger Factors in Episodic Migraineurs Using a Smartphone Headache Diary Applications. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0149577.

- Lipton RB, Dodick D, Sadovsky RE, Kolodner K, Endicott J, Hettiarachchi J, et al. A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care: the ID migraine™ validation study. Neurol. 2003;61(3):375–382.

- Láinez MJ, Domínguez M, Rejas J, Palacios G, Arriaza E, Garcia‐Garcia M, et al. Development and validation of the Migraine Screen Questionnaire (MS‐Q). Headache: J Head Face Pain. 2005;45(10):1328–1338.

- Steiner TJ, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Linde M, Macgregor EA, Osipova V, et al. Aids to management of headache disorders in primary care (2nd edition). J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1).

- Do TP, Remmers A, Schytz HW, Schankin C, Nelson SE, Obermann M, et al. Red and orange flags for secondary headaches in clinical practice: SNNOOP10 list. Neurol. 2019;92(3):134–144.

- Sacco S, Bendtsen L, Ashina M, Reuter U, Terwindt G, Mitsikostas DD, et al. European headache federation guideline on the use of monoclonal antibodies acting on the calcitonin gene related peptide or its receptor for migraine prevention. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1).

This content has been developed independently by Medthority who previously received educational funding in order to help provide its healthcare professional members with access to the highest quality medical and scientific information, education and associated relevant content.