Transcript: Liver disease in ATTD symposium

Rohit Loomba, MD; Pavel Strnad, MD; Alice Turner, MBChB; Virginia Clark, MD

All transcripts are created from symposium footage and directly reflect the content of the symposium at the time. The content is that of the speaker and is not adjusted by Medthority.

So this is our topic for today, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency liver care journey: From early signs to effective strategies. This is a satellite symposium here and this is our joint accreditation statement. And thankfully I'm now gonna read this so you can take a look at that. This is our faculty today, we have Paul Strnad, is a professor of medicine at University Hospital Aachen in Germany. Really a international leader in this disease area. I am Rohit Loomba from University of California, San Diego. And then Alice Turner who's a pulmonologist, also a professor of medicine at University of Birmingham in UK. And she just told me that she's gonna be leading a very big research center which will be multidisciplinary, one of the fifteen of such centers in UK. So congratulations on that center at Birmingham. And then Virginia Clark, who's professor of medicine at University of Florida, really been leading the efforts on alpha-1 antitrypsin related liver disease. Done a lot of work on natural history and treatment trials in the United States. So we're really lucky to have a great panel. And over the last 10 years I've learned a lot from my panelists about this disease area and a lot of new advances are being evolved over the last 10 years, and we're really excited about many of them and discussing those advances today. So this is our agenda today.

We'll start with a brief introduction, followed by Pavel's talk on how does alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency impact the liver? Then I'm gonna talk about how we're gonna find these patients in our clinic. And then Alice Turner would talk about whose patient is it anyway in terms of collaboration between the pulmonologist and hepatologist. And then Virginia Clark will discuss how can we best manage alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency-associated liver disease and also discuss it, discuss novel therapies related to alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, specific to liver disease treatment. And then we will take your questions and answers, and discuss those and wrap up now in an hour. These are the objectives of our symposium.

So this is our first polling question. "How many patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency do you see in your clinic annually?" A, zero to 10. B, 11 to 20. C, 21 to 30. D, more than 30. Okay, great. That's very nice. So we have many of you who have, who are seeing patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin related liver disease in your clinic, and some of us have more than 30 patients in the clinic, 16 of us. That's really fantastic. So, I think there's a lot of knowledge and expertise in this room. So we're really glad that you are here and we look forward to your questions and engagement. Now I'd like to invite Pavel Strnad, a Professor Internal Medicine and University Hospital Aachen to talk about how does alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency impact the liver? Pavel?

Thanks Rohit for setting the stage. It's my pleasure to get some liver edge before Alice comes and brings us back to the lung. These are my disclosures. So to understand what alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is, you have to remember that the function of the liver, one of the major function is to basically produce pretty much all the proteins that we have in the bloodstream. The big one is, obviously, albumin that we all know, but albumin has a little brother, which is called alpha-1 antitrypsin. And that's doing, having the same fate. So it is built in the liver in the endoplasmic reticulum and is secreted through the Golgi apparatus into the bloodstream to act as a antiprotease. So to protect our tissues, particularly the lung from the digestion. And if this fails as a consequence of inherited mutations, we end up with obvious alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

That means that in the liver, the secretory pathway is basically clogged up and we have this accumulation of this protein which is supposed to thrive in the bloodstream, and instead of that it got stuck in the liver. So that's in a nutshell what alpha-1 antitrypsin is. There are more than a 100 different alpha-1 antitrypsin mutations. Luckily we only have to remember two of them and that's the Z and S. The Z one is here the predominantly severe mutation and because of that, the homozygous mutate, Z mutation called also Pi*ZZ genotype is responsible for the majority of severe alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency cases. It's relatively rare in Caucasians in, it's about one in 3000, but it's kind of the really sick patients. And if you have this ZZ mutation, you can have a liver disease at two different stages or at two different times. First of all, a small majority of kids develop first early onset neonatal jaundice. So kind of they, their bilirubin degradation and so on doesn't work somehow an excretion, and the natural jaundice that every kid has is prolonged. And out of these kids, few percentage have a continuous disease that needs a liver transplantation.

Usually this is really a disease that manifests in the first age, years of age. If the kids somehow learn how to live with it, they usually get better in time. And then the other people get a liver disease usually in a second half of their lifespan about 40 years old or later. And it's a classic kind of metabolic disease as, Rohit, can tell you everything about which if you have additional risk factors like obesity to diabetes may be also drug induced issues, then you are even at a higher risk. And about 10% of these patients end up with a liver fibrosis and about quarter of them get a significant liver fibrosis. So this is a large population based study where basically it was only looked at the liver function tests in these patients until, as you can see the alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency patients on average have a little bit higher transaminases, both ALT and AST, but the difference is very small. And if you take the whole population of the ZZ patients, only 10 to 15% of them have actually elevated liver transaminases, which means vice versa. If you have a ZZ patient with regularly elevated transaminases, it means that you have to really pay attention, consider what are the reasons and really make sure that this patient doesn't get into troubles.

Despite the fact that these patients don't have or often don't have elevated transaminases, they have strongly increased risk of liver fibrosis. This is the same database where when you look at advanced liver fibrosis or cirrhosis, you get about 20 times increased risk of that and even higher risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. And this is much higher than the usual genetic variants we kind of talk about a hepatologist like PNPLA3, TM6SF2 or whatever your favorite genetic variant is. This is the largest existing study from Ginger that they deliver biopsy on about a 100 of Pi*ZZ patients and compound lung and liver phenotype. And you can see here two things which are important.

One is that in this study, 35% that means even more of these patients had a significant liver fibrosis and there was really no kind of association between lung and liver disease. So you can have a patient with a perfectly normal lung and then advanced liver disease and vice versa. And that's why, Alice will talk more about that these patients really need both organs being checked. And another thing which is nice about this study, it showed that as the liver disease progresses, the accumulation of this toxic alpha-1 antitrypsin increases. So there seems to be some kind of vicious cycle that as the liver gets more sick, it has more and more difficulty to handle this misfolded proteins and gets more and more of the accumulation. So the question is how we actually know that this is a proteotoxic disease and this, there is a new one that I study which I wanted to briefly introduce you. So the best way to really understand the consequences of these protein accumulation is really to take cells with and without these proteins and compare them. And this you can nowadays due to advanced proteomic techniques, and this is what was done here. So we used laser capture microscope. So with laser we cut these cells with different aggregates and when you compare cells with and without aggregates, you get a huge difference in the biochemical pathways.

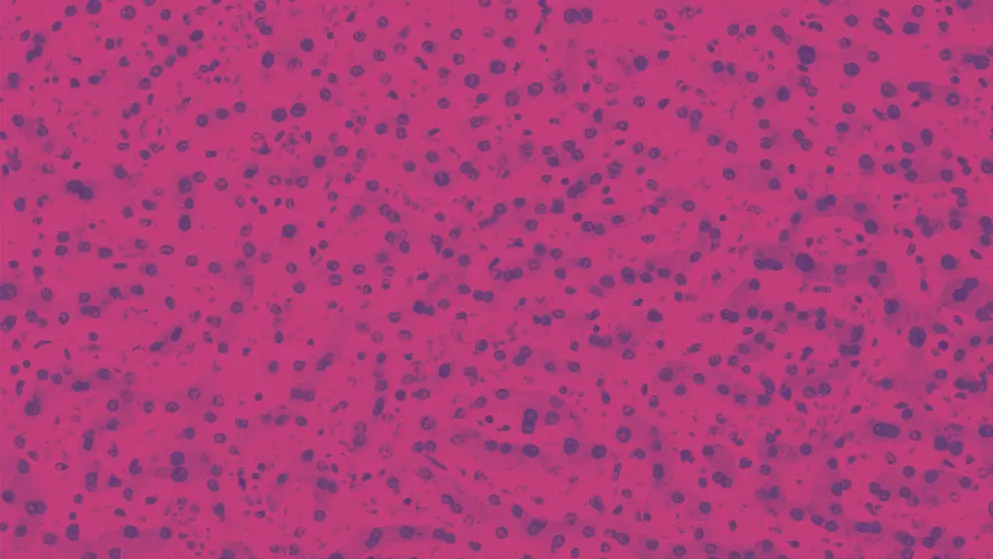

This is just the control for SERPINA1 showing that this really work, that kind of the cells which should have a lot of alpha-1 really have a lot of alpha-1. And when you divide these cells in this way, then you see that the cells which have a lot of alpha-1 antitrypsin have also different apoptotic pathways turned on but also ER stress. So this is actually a very nice kind of scientific proof that and that cells that have the aggregates are either the ones and that are suffering. So this brings me to the end of my presentation and I'll summarize these three things. I hope you to remember when you go out here and the the food is flowing in. So the ZZ genotype is really the one we have to take care of because they have a high markedly increased risk of fibrosis, cirrhosis and primary liver cancer.

We have to keep in mind that the patients with elevated transaminases are the ones where we have to dig deeper because they seem to have some problem and that the lung and liver diseases are independent on each other, and that the liver disease gets asymptomatic as until it's too late, but that's whatever hepatologist knows. Thank you.

We'll start with the patient journey and so you'll meet John shortly. He's a 68 year old asymptomatic patient with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

My brother was actually diagnosed prior to me finding out and that's basically how I found out that I had alpha-1 was because my brother found out, and the rest of us siblings were tested and we all were diagnosed with alpha-1. I wanna say it was about 2013 but I wasn't showing any symptoms at that time. I was going to the doctor, they were testing my breathing, they were testing my liver. They did a liver biopsy and they found that on a scale of one to four, my liver was at about a one or 1.5, and I really wasn't showing any symptoms up until 2021.

So this is not very, you know, atypical that majority of our patients, you know, may not even know that they have a liver problem and they're asymptomatic particularly early on in their disease until they develop cirrhosis. So how can we detect our patients in the clinic or those who would be at risk and how can we develop protocols so we can diagnose individuals early and then think about, you know, risk reduction and monitoring. These are my disclosures. So in this slide what we are looking at is patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency related liver disease.

If you look at those with Pi*ZZ adults, depending on if they're never smokers, you can see 36% cause of mortality, respiratory diseases followed by, you know, hepatic disease and the cardiovascular disease. And then those who smoke, of course the risk of pulmonary disease goes up, but there's pretty significant risk that remains for liver disease and also cardiovascular disease. So in patients with Pi*ZZ, liver disease is really an important cause and I think majority of these patients are never diagnosed, and that's something that we can do something about as hepatologist.

These are some of the predictors of advanced liver disease in patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, of course high BMI elevated ALT, elevated alkaline phosphatase, elevated INR, low platelet count, abnormal echogenicity of ultrasound, splenomegaly, and then severity of lung disease. If you think about all of these, these are common across all chronic liver problems. So you may diagnose somebody with fatty liver but never test for alpha-1, you may never know that patient actually may have alpha-1 antitrypsin related deficiency. So the only specific factor here is severity of lung disease.

So a patient who has emphysema, we should really start thinking about testing for alpha-1 antitrypsin. All those patients who have emphysema, if they have elevated ALT or any of these other features, they should be tested. Of course family history would be really important, just how our patient talked about brother got diagnosed and that's how the patient got tested. So I think we, this is a two step phenomena. First, detecting ZZ status and second, looking for liver fibrosis or liver disease. If we already know somebody has ZZ based upon a pulmonologist or lung disease or being seen in a pulmonary clinic, then testing for liver disease in our clinic would be really important. And these are some of the data that have been actually developed at, you know, three of our centers. And I'll show you these studies that provide really good evidence as to how we can use non-invasive tests to identify patients who may have a more severe fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with lung disease.

So you can see, of course, elevated ALT is important, elevated Alk Phos, platelet count less than 174 would be important. Abnormal liver echogenicity, I think this is something that comes up a lot. Many times these patients might get labeled, initially, as fatty liver. So I really want us to be thinking about that all those patients with fatty liver, there might be rare diseases that are genetic, particularly alpha-1 that may be hiding within that. So we probably need to do some sort of a systematic assessment. Anybody who's getting in with fatty liver disease, particularly if they have significant fibrosis or elevated liver stiffness, at least test them for alpha-1 antitrypsin, ZZ status. And splenomegaly, of course, that would be later in their disease when somebody has developed cirrhosis, but all these are important factor for any advanced liver disease or cirrhosis across a spectrum. But really important for detection of occult alpha-1 antitrypsin related liver disease in the setting of a lung problem.

Of course FIB-4 is something that we are routinely using across a spectrum of chronic liver diseases, and this includes age, AST, ALT and platelets. I already showed you that all those would be important in finding if our patient has disease. To simplify things that across a spectrum of liver problems we can use one test to start thinking about advanced fibrosis. You could take the framework of FIB-4, if it is below 1.3, again, this would be a low risk for advanced fibrosis, but if it is 2.67 or higher, predicts higher likelihood of advanced fibrosis. The idea would be anyone with a FIB-4 or 1.3 or higher, we should start thinking about that this patient may have significant fibrosis and potentially could be a candidate for a clinical trial with alpha-1 antitrypsin as Ginger will discuss that many of these agents are now in clinical trials as well.

This is looking at liver stiffness based upon data from Pavel's team, where they looked at Pi*ZZ carriers versus non-carriers. Of course greater liver stiffness because they have higher likelihood of fibrotic disease. What about APRI value? Again, those were also higher and HepaScore as well, which is a direct marker of fibrosis. So just saying that just having ZZ status really increase your risk for fibrotic disease. If you look at the number one genetic cause for cirrhosis in terms of gene and its impact, it's SERPINA1 which is the alpha-1 antitrypsin related liver disease, across spectrum of all genetic causes. This is also something important to think about in terms of odds of advanced disease. So patients who have ZZ status or carriers, they have 20 times higher odds of having liver stiffness of 10 kilopascal or higher. Why are these data important? Well this tells us that it would be cost effective if somebody had alpha-1 antitrypsin ZZ, that we should be doing a FibroScan to assess for it if we have MR Elastography to assess for that or use an APRI or FIB-4 at least to look for those who have advanced disease or advanced fibrosis.

This is data looking at liver stiffness at baseline and liver related endpoints. And you can see if the liver stiffness was below 7.1, of course no significant endpoints, but you start seeing those that have liver stiffness on FibroScan from seven to 10 kilopascal, you start looking at those patients accumulating events over a long period of time, followed by those with liver stiffness, 15 kilopascal higher. These are particularly are potentially patients with cirrhosis or stage three fibrosis, significantly increased risk for liver related outcomes. APRI is also helpful and so you can utilize that also to think about which patient may have fibrotic disease. All these will become more and more relevant as newer therapies come to clinic. Now I'm showing you data, I already showed you the top panel which is liver stiffness and liver related endpoints, but here's showing you that FEV1 is also something that's important. This is looking at lung disease. So I think it's also important if we see a patient with alpha-1 antitrypsin and diagnose them in our clinic, it's important to refer the patient to a pulmonologist so they can get their lung disease evaluated as well. Because long term outcomes related to lung disease are also increased in our patients based upon their pulmonary status, based upon FEV1.

There was a recent Delphi panel that we conducted along with collaborators across multiple continents, and we came up with this algorithm based upon that Delphi panel. So, you know, if somebody has a known family history, or genotype, or phenotype testing results indicating alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, patient getting referral from a general practitioner, pulmonologist or their specialist. For a hepatologist and gastroenterologist to establish the diagnosis of AATD, we wanna think about patient education, family education and then think about staging the disease and monitoring of their disease. So any patient who has elevated ALT and AST, should think about whether this patient may have alpha-1 antitrypsin, particularly in the setting of family history of liver disease or cirrhosis, family history of liver cancer, family history of lung disease, personal history of lung disease. Those patients are at very high risk for having alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. So we should order testing and look for ZZ in them. Once we've established that, then the next step in our clinic would be liver stiffness assessment based upon the Delphi panel, and then based upon the VCTE based upon this consensus, if the liver stiffness was eight kilopascal below eight kilopascal, you could reevaluate in two to three years, that would be reasonable. And if it is between eight to 13 kilopascal, you wanna follow them at least eerily, you could consider additional NITs. We talked about MR elastography enhanced liver fibrosis panel or liver biopsy if discordant results across two or more NITs. If liver stiffness is 13 kilopascal higher, or APRI suggestive, or FIB-4 is very high, or imaging, or ultrasound evidence of portal hypertension, or if you end up doing a biopsy, those patients may be more closely monitored, particularly if you think they have cirrhosis. Once you develop cirrhosis, you monitor a patient based upon their MELD score and you also want to be doing at HCC screening and surveillance because risk of liver cancer is very high in our patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin. If MELD score is not more than 15 or they don't have decompensated disease, I think you wanna monitor our patients, and if the MELD score is 15 or the hepatic decompensation, you could consider liver transplantation.

So I think this framework is helpful as we think about how we would manage these patients in our clinic and monitor them. And this is based upon consensus of about 30 experts who had different expertise related to this area. In summary, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency associated liver disease, one of the most important genetic and familial causal liver disease and cirrhosis. Patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, certain lung disease should be screened for liver disease and liver fibrosis. You could do a step one approach with FIB-4 or APRI and the step two could be liver stiffness by either FibroScan or MR elastography. You could use ELF for other fibrosis markers as well. Obesity, alcohol use, diabetes and smoking increase the risk of progressive liver disease in our patients.

So this is actually my fourth EASL, so I'm a pulmonologist intervening, but I see a lot of alpha-1 patients about 10 a week.

So these are my disclosures. And what are we aiming to cover today? So we'll talk about a case from my practice. So I do routinely assess the liver in all of my new patients to clinic and then adjust their follow up regime accordingly. And I like to try and be patient centered in my practice. So would I, if I was a patient, want to come back twice where maybe I could come once? And the answer to that is probably not. So how much of what I, how much of the liver practice can I incorporate into my clinic for those lower risk patients? And what could you as liver doctors do to incorporate the basics of lung disease management just to make things better for your patient?

So, patient from my practice, 75 year old gentleman with Pi*ZZ alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency but known to me because he's got very severe COPD. So he's been under follow up in my center for more than 20 years and I'm not quite that old, he was under somebody else before me, but it he, I inherited him and at this point I escalated his treatment and we inserted a one way valve into his lung in 2019. And what this does is decompress the lung to allow a little bit more room as I would say to patients for the less damaged areas of the lung to work so that he could breathe better. But he is also got atrial fibrillation, he's got heart failure with an ejection fraction of 40% and he is known to have prostate cancer which is adequately managed with hormone therapy.

This is his lung function here. So his, these are these values, probably the easiest way to look at them is the percent predicted. So the percent predicted is what he is relative to a normal person of his age and height. So you can see his FEV1 is 35% predicted that puts him into the severe range, normally between 30 and 50 is severe. But you can see that his gas transfer, the TLCO is down at 17% predicted. So that's really what sort of made him a very severe patient. He has not got any additional risk factors for alpha-1 liver disease. He doesn't drink anymore. His BMI is normal and has been throughout the time that he's been under follow up. He's not known to have any metabolic complications.

We first started to introduce FibroScan into my clinic routinely in 2018, a year after my first EASL when I first presented some of the early siRNA data, and at this point his FibroScan was clearly abnormal. His liver function shown on the screen and at that time we were able to send off ELF in our clinics as well.

I was running a joint liver lung clinic with one of my colleagues, professor Phil Newsome, and so we saw him there for annual follow up thereafter. And his ultrasound is shown from 2021. More recently he's been declining, he's had some weight loss, he's been admitted with what were thought to be heart failure symptoms, edema, essentially, and an increase in exacerbation. So this is more breathlessness essentially. So people would assume that this was to do with his lung disease but maybe it was actually to do with his liver as well. So I'll just let you glance at these. So this is, essentially, a screenshot of our electronic healthcare record, showing you his elastography results over the years from 2018 through to present day. So you can see we were doing him sort of every one to two years throughout this time and that his score has been gradually going up throughout. I don't intend to read this for you but this is a screenshot of his liver function tests.

So in this, the abnormal results for some reason pop out in red or blue depending, so some of the abnormal ones are shown in red and some of them are shown in blue, but depending on whether they're high or low. So you can see he's got some abnormalities in his liver function. His gamma GT has been going up, his platelets have been going down. Just to go back to his lung disease and to give you a little bit of a primer about it. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency lung disease is really common. It occurs in about 80% of patients who've got the ZZ genotype, and 50% of patients with a more mild form of deficiency with the SC genotype. Clinically presents as panlobular. So that means where it's very widely destroyed lung as you can see in the picture, and it's more predominant in the lower zone but it can present throughout the lung as well. And patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency are more susceptible, essentially, to smoke in environmental insult.

So you need to ask about occupational exposures, cigarette smoke, all the other inhaled things that people may be exposed to in life. So pollution probably makes a difference, but typically cigarette smoking is the biggie. You've got COPD if you've got an FEV1, FEC ratio of less than <0.7 after being given a bronchodilator, and COPD and emphysema I would say to patients is sort of like two sides of the same coin. They're not exactly the same thing but they do have quite a close relationship to one another. Other parameters that you can look at on the lung function, you can look at lung volumes and you can look at gas transfer, and gas transfer tends to go down when the emphysema is particularly severe, but also in the presence of pulmonary hypertension. And you can get other lung diseases as well.

So we've recently shown that bronchiectasis can occur in Pi*ZZ patients and this is independent of the occurrence of COPD. Lung function decline is historically thought to be faster in patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and you need to monitor that regularly to pick it up. So here you can see a summary of a variety of different studies that have been done looking at FEV1 decline, specifically. FEV1 decline is looked at more often, often because it's basically just easier to measure, but you probably need to measure it at least three times over at least three years to get an accurate measure. So some of these measures are arguably not as accurate as they could be, but you also see great heterogeneity. So in my own ZZ cohort that values of which is shown at the bottom of the screen, initially one of the papers describing this cohort was rejected saying your patients can't be deteriorating this slowly. I was like, well thanks very much, they are doing okay but actually one of the reasons why my cohort looks like it's better is that 25% of my patients are diagnosed by family screening and are completely asymptomatic, and 25% of them have got very severe COPD where their FEV1 is always, already less than 30%.

They've got nowhere else to go in terms of bottoming out. So that's why the overall number looks not so bad but if you look in the middle range you can see that they're deteriorating about the same as the other cohorts that you can see in the table. So what can a hepatologist do when they see a patient with alpha-1 that they think has got some lung disease? Well we can all do basic stuff. You don't need any special training to tell somebody to be able to stop smoking and do some basic stuff about lifestyle, including vaccines and exercise. Pulmonary rehabilitation for example, very good treatment for lung disease, really cost effective as well. And you can give some basic inhalers. So every patient who's got COPD should be on a dual bronchodilator, a long acting muscarinic antagonist and a long acting beta agonist which come in a combined inhaler these days, and if they've got exacerbations regularly, you would add a steroid to that as well. So I think that's something that pretty much everybody can safely do, whilst we then get the more specialized tests.

There are some good reasons to go and see a pulmonologist as well though. In many areas of the world, not sadly in my country, but in many areas across Europe and worldwide, you can give augmentation therapy. So this is replacing alpha-1 in the system, so you deficient patient replace the alpha-1. And what you can show in the meta analysis of the various randomized controlled trials that have been done over the years is that if you give this therapy you will reduce the deterioration in lung density.

So you saw a picture of a CT scan, you saw a reduced lung density in the emphysema areas that will not get as worse as fast if you give augmentation, but you can't detect that if you use standard lung function measures. And this is probably just a power related phenomenon. We do see reproducible benefits on mortality.

So on this screen here are two completely independent studies, one done in Ireland and a composite of a couple of other European countries including Switzerland and Austria and one on the right comparing the UK, and the USA. And the UK and Ireland didn't have augmentation therapy available and their patients, essentially, are dying faster than the patients in the countries that are using augmentation routinely. If you look closely at some of the numbers in terms of where those lines start to diverge, they are actually reasonably reproducible, particularly when you consider the differences in the healthcare system. So lung disease gets worse slower, people live longer. So what should the hepatologist do? The basics, as I've already mentioned, but what you can also do is actually put in place the tests that maybe the pulmonologist would like to look at. Lung function, either annually or, well, annually in everybody really, but with some imaging in your symptomatic patient and referral, particularly where you're considering augmentation therapy. How's my service structured to make it patient centered? So I'm set up so that my clinic can do FibroScan. So we have that available for all of our patients and we keep essentially the low risk patients in my clinic and it's only when they're deteriorating or they've got risk factors that we progress them to seeing two physicians together. We also have trained the nurses up in the liver based service so that they can do spirometry in the liver based service. And so we have a sort of way of both of us manage our low risk other organ and then the high risk dual organ people we see together.

So to summarize, what should we do for our patients? We should make sure that all of our symptomatic patients have got full lung function tests. So that means spirometry, and gas transfer, and lung volumes. We should offer smoking cessation, lifestyle advice and we should consider augmentation therapy. Patients with asymptomatic lung disease need annual monitoring, and we should definitely try and work together better so that we can be offering a patient centered service. Thank you.

So we're gonna go back to John's journey and looking at appearance of symptoms and management of liver disease.

There was a lot of ups and downs, I'll tell you that. My first symptoms showed up in December of 2021. Those, that symptom wasn't breathing problems, it was my portal hypertension was really, really high. And what it did is I started to swell up with the buildup of fluids in the abdomen. The first time I went to the hospital to get a paracentesis, they drained about three liters of fluid. Then the timeframe from the first time to the second was about four and a half months. From the second time to the third time it was only about four to six weeks. Portal hypertension had gotten to the point where my stomach was actually the veins in my stomach were, forget the term that they used. They were swollen and bloated to the point where I was actually bleeding internally into my stomach. They admitted me through the emergency room and that's when they pretty much figured that I was going to need a transplant.

So now we're gonna invite Virginia Clark to talk about management of this liver disease due to alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, okay? Press this.

Okay, we are definitely finishing with the shortest speaker of the day. Thank you guys all for hanging in there and staying with us. So my talk today, here are my disclosures.

We're gonna focus on the final learning objective of the talk today. And it's really to describe the current and future associated liver disease management strategies. And it's easy because there's not really a lot of management available, management for alpha-1, but I will commend that EASL and they have published really the only clinical guideline that was published last year. It's the EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on genetic cholestatic liver diseases.

And within that clinical practice guideline it talked about diagnosing alpha-1 monitoring for liver fibrosis, and then a recommendation really on disease management. And it's the only liver specific disease management that's out there. And you've heard this already in every talk, which is lifestyle counseling, right? It's what we can do for these patients, which is to tell them not to smoke or stop smoking, to manage their weight effectively and to limit alcohol consumption because of the negative health impacts that these can have on individuals with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

What we all know, and have probably have, we've heard from John who's was my patient has, that liver transplantation is the only effective therapy for individuals who have advanced liver disease in alpha-1. And I show you this data from, this is a large retrospective series that was from France and from Switzerland, combined data looking back over many, many years. And what really jumps out from the graphic is that there's a bimodal distribution of liver transplantation in this patient population. You can see on the far left that in the pediatric population from zero to age 15, a large number of individuals who were transplanted for alpha-1, and then another peak that starts around age 46 and goes up to about age 65. And that's the adult patient population that's transplanted what has been pretty remarkably stable. This is the same phenomenon I seen in the US, I'm just showing the data from Europe, is that the number of transplants over time for alpha-1 has remained relatively stable. But what has happened is a shift in the epidemiology so that this is really an adult disease now, because less and less children are being transplanted. And the ABS in terms of absolute numbers of who's actually transplanted for alpha-1 and trypsin deficiency, it's actually focused in the adult population. The good news about it is that liver transplant has excellent, excellent, especially compared to some other disease etiologies in adults, it has excellent long-term survival.

Looking back you can see these patients were followed I think a median of around 13 years. But you can see as far out to 20 years that adult survival is well over 75%, both for overall patient survival and for post graft survival. I will say though that transplant can be, in a patient population that has both liver disease and lung disease and we know that they overlap in a certain percentage of the patient population. A very thorough pulmonary exam like you've heard is important for, before you consider someone for a liver transplantation. And we all maybe have seen a patient who had decompensated liver disease and who was deserving, or could be considered for a liver transplant but had such severe lung disease and maybe wasn't a candidate for a lung and liver, which is really uncommon being denied the opportunity for transplant because of the comorbidities. So, what the next portion of this talk really is focused on is kind of what's coming in the future, very kind of forward looking talk, and it's focused on what's out there. And some of this is really very early data, but all of what I want to convey to you is that all of the mechanisms of these drugs that have been evaluated are focused on decreasing the proteotoxicity. You've heard about that it's the accumulation of the misfolded alpha-1 protein that causes the liver disease over time. And then when I think about the types of therapies that are out there, the kind of three big buckets I would put them in. The first is gene editing, where directly intervenes on the DNA at a DNA level. And the second is RNA editing of which you have siRNA or RNA editing directly. And then the third category would be folding correctors.

And then some of you who may be familiar from the, with the field know that some of these drugs that are listed on here have their development has been discontinued. And we'll get, I'll talk a little bit more about that. So why is there excitement really around gene editing? It's because gene editing therapy can really address the underlying disease. It goes right for the mutation. And if you can correct the mutation and produce a normal wild type protein secretion, then it's, we might consider this something close to a functional cure.

So what that means would be the, that the, there would be normal secretion of the M-AAT to protect the lungs. You would, the normal alpha-1 would get out of the liver and there would be less accumulation. And I think the one of the more, probably the higher bar to set and to meet would be that if you had a gene editing therapy, you could actually potentially restore the ability, because alpha-1 is an acute phase reactant. So if you get an infection, you get inflammation. The amount of production in alpha-1, four alpha-1 that your liver does rises to meet that challenge. So this is something that augmentation therapy can't really, really replace. So recently this proof of concept, where are we, how close are we really to gene therapies? I think we have proven that it might can be done, but we're ways away from a cure. So this was presented, I think it made a big splash in the New York Times, but is also presented in other places. BEAM-302 basically there, the mechanism that they have developed is it's clever, it's going right after the DNA, it's a modified CRISPR protein with an RNA guide with deaminase attached to it.

So you can see in the top cartoon the Z, you see the A, that is the single point mutation at which the gene therapies edited to correct. So in the, in their mechanism, what happens is the A is translated to an I and you get in the normal protein, you get a GC, which is what it's supposed to be. So in proof of concept, they've dosed, this has been dosed in nine patients. So to keep that in mind is just nine patients and a dose escalating early study at 15 milligrams then 30 milligrams, and then 60 milligrams. And this is, I'm showing you the data that's in public out to 30 days basically. And you can see a dose response curve, which is what you'd like to see in an effective therapy. And then more importantly, at the 60 milligram dose, what you may not be able to appreciate is that there's a line, a protective threshold, which is what our pulmonary colleagues say is above 11 microgram per molar that your lungs will be protected from any damage. And at the highest dose, this base editing mechanism was able to achieve that protective threshold.

There's a lot of unknowns, obviously there's a lot, there's some excitement around the data but the durability, the sustainability, the side effects, a lot of, a lot remains to be seen. But it is interesting in the proof of concept that for a direct base editing mechanism in vivo, it's out there. And alpha-1 is a nice model because it's a monogenetic disease with a single genetic change. There are other mechanisms that may target gene correction and RNA editing is another approach because it, but it's focused more at the transcript level. So the idea behind this type of therapy is that delivery of an nucleotide that will edit a very specific identity and target on the target, RNA, very similar in approach, but then what you end up with is the oligo RNA duplex recruits the intrinsic ubiquitous ADAR and that's in human cells. And then we'll convert it automatically from an A to an I. So what you end up with is a normal messenger RNA that reads out as the therapeutic protein for MM. So this is not quite as far as long, this has been shown to be effective in the laboratory and mice models. But we're, now it's just going into the first phases, very early phases of clinical trials. And there are two companies kind of in this space, enrolling these clinical trials now and they'll be designed much like early phase clinical trials are as a dose escalation, proof of mechanism, type of studies. Now the reason that RNA editing might be a more interesting approach than DNA editing is because it's in theory it's reversible and you can maybe apply it in a little bit a manner across a broader severity of disease, and it avoids the permanent kind of off target potential complications when you're editing the DNA directly.

So now what is out there and what's more advanced is fazirsiran, which is an siRNA therapy, basically a gene silencer. And there have been published studies, two published studies, one from an open, a phase two open-label trial and then one from a phase two, a randomized control clinical trial. And both showed very think convincingly that this is a mechanism in which you can, if you turn off the production of alpha-1, then you can lower the concentration of the toxic Z-AAT accumulation within the liver. And what I'm showing you here is the both the individual data in the purple from patients at baseline, their total liver Z-AAT content before treatment and then after treatment.

And then you see the mean changes in the difference. And so overall compared to when they, this on the open label trial, there was a median reduction of 80 by 83% at the end of follow up. And all, that also was reflected in a reduced serum level of AAT by 90% at the end of follow up. And overall there was a on pathology, a reduced histologic globule burden and the liver enzymes also improved. Now this study wasn't really powered to look at fibrosis because it was, this was a total of 16 patients that were enrolled. And going on at the same time was a randomized controlled trial called, SEQUOIA, and looking at similar but similar outcomes but with a placebo group. And you can see the total liver Z-AAT content was comparable between the placebo group and the treatment group at baseline. But then at follow up after therapy, the, there was a 90, approximately 94% reduction in the total liver Z-AAT after treatment and the placebo group went up. This was also clearly shown in looking at the histology. You could see by globule burden, pictorially, I think a picture is always worth a 1000 words. You can see at baseline how much of the alpha-1 in these classic PAS+D globules were present, and then after treatment, what was left in the liver. And it was really remarkable that not much was seen. So an effective therapy at clearing the globulin burden out of the liver. And this drug is now moved into phase three and is actively recruiting kind of for a worldwide trial to look for therapeutic benefit. So, and then the final bucket in terms of overall, how are we gonna approach therapy in the long run is an idea. This is in the post-translational modification of the protein because what happens with the genetic change is that the protein gets sticky, it sticks itself together, it misfolds and it accumulates. So if there's a way, a mechanism, a therapy that could help the protein fold correctly and get out of the liver, then that would be also and be functional. That would also be a holy grail.

So, there was a several compounds that Vertex was developing and phase two and in phase one that looked at this concept to prevent polymerization aggregation and improve secretion. But, unfortunately, they can couldn't show that they could raise the level to get out of the liver and to a level that would be protective of the lungs. So both, so this program has not, is not being further developed. And then another company is just early, early entered the phase and of looking at a potential corrector for protein misfolding. So we don't have any data yet for this, but we'll, to be determined. So there's a lot of approaches to this genetic condition that are out there.

For summary, liver transplantation is the only approved treatment for liver disease in alpha-1 antitrypsin, but there, it's exciting times now when the potential, we have phase three clinical trials and active for an active therapy and then on the horizon gene editing and RNA editing to correct our alternative to treat liver disease. And so we're gonna eventually be able to see therapies that can reduce this proteotoxic burden and maybe even come close to functional cure. Thank you very much.

Thanks Ginger, I think we're at 2:30. We are happier to take some questions? Question one, can you clarify if you use serum levels of alpha-1 antitrypsin as a determination of whether you perform genotyping as part of your liver screening? Will cases of Pi*ZZ or Pi*SC be misusing this strategy? Pavel?

So the ZZ are quite distinct, so they have really 85% reduced serum alpha-1 level. So there are obviously exceptions, but if you use a cutoff of 50 or so, which is recommended in the EASL guideline and others, you should really not miss ZZs. Of course you should measure outside of the inflammatory conditions. So that may make it even easier but the 50 is quite safe for ZZs. The SZs are a little bit higher than can be about 60 or so if you want to detect SZs, you probably have to get a cutoff of 80, 90. You still have a good chance for the MZs that is no perfect cutoff. So for the severe ones it's easy and for the less severe ones it's getting difficult.

That's great. I'll take a few more, how often do you recommend to do the FibroScan? We know the transaminases are not very good parameters to evaluate the damage. So every two years or every year. So based upon the consensus you do the FibroScan first time, if it is below seven kilopascal, then every two to three years is fine. If it is more than seven or more than eight, then you wanna do once a year. And that would be reasonable. Once somebody develops cirrhosis, make sure to do the ultrasound because FibroScan alone is not enough. You wanna look for HCC screening, surveillance and if they develop portal hypertension or features of it, then endoscopy and monitoring for ascites, management of ascites, looking for hepatic encephalopathy, managing for that, and then refer for liver transplantation. We'll take one more. Should Pi*ZZ patients be with normal ALT, get fibrosis assessment or further evaluation? So, patients can have normal ALT, but they may still have elevated APRI or elevated FIB-4. So depending on the health system you're in, if it is a system where the access may not be there, then you can consider waiting for a FIB-4. And if the FIB-4 is 1.3 or higher, that would be reasonable to do a FibroScan in that patient. In United States, typically every ZZ will at least one time do a FibroScan to establish where they stand, and we already discussed based upon if they were below seven or greater than seven what we would do in terms of their follow up. So with that I would like to thank all of you for sticking around with us and to our panelists. Thank you.

Developed independently by EPG Health, which received educational funding from Takeda, awarded to EPG Health to help provide its healthcare professional members with access to the highest quality medical and scientific information, education and associated relevant content.

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Amedco LLC and MEDTHORITY. Amedco LLC is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Amedco Joint Accreditation #4008163.

Professions in scope for this activity are listed below.

Physicians Amedco LLC designates this enduring material for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 CreditsTM. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.