Alopecia areata management update

In this section

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of alopecia areata (AA) can be a long and complex process, with delays negatively impacting the emotional wellbeing of those affected.1

Patient advocate Lynn Wilks describes her experience with diagnosis and the emotional impact it had on her. View transcript.

Clinical features

Brett King (Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA) provides an overview of AA diagnostics and its challenges. View transcript.

Scalp hair loss in AA is most commonly patchy with clear edges and complete loss of all terminal hairs in at least one area. The disorder is clinically classified according to the skin areas involved, the pattern, and the extent of hair loss (Table 1).2

Table 1. Clinical variants of alopecia areata and their characteristics.2

| Clinical variants of alopecia areata | Presentation |

| Patchy alopecia areata | Single or multiple circumscribed, well-demarcated patches of hair loss on the scalp |

| Alopecia totalis | Complete scalp hair loss |

| Alopecia universalis | Complete loss of facial, body and scalp hair |

| Ophiasis alopecia areata | Hair loss on the occipital and temporal scalp site |

| Inverse-ophiasis (or sisaipho) alopecia areata | Central hair loss, lateral and posterior scalp sites are spared |

| Diffuse alopecia areata/Alopecia areata incognita | Diffuse hair loss and reduction of hair density |

| Alopecia barbae | Discrete circular or patchy hair loss areas in the mustache or beard, often along the jawline, rarely diffuse thinning |

| Alopecia areata of the nails | Nail pitting, trachyonychia, red lunula, longitudinal ridging, onychomadesis, onycholysis and onychorrhexis |

Clinical assessment of the rest of the body can support diagnosis by revealing symptoms beyond scalp hair loss, including loss of body hair, eyebrow hair, and eyelashes, and pitted nails.2

AA can be diagnosed clinically, but tools such as the pull test, trichoscopy, and histopathology are often used to ensure an accurate diagnosis.2 Severity of hair loss is assessed through a variety of standardized clinical scores, such as the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT), SALT II, and the Alopecia Density and Extent (ALODEX) score.3

Differential diagnosis of alopecia areata

To ensure appropriate treatment, it is important to distinguish AA from other conditions that cause hair loss. These include tinea capitis, trichotillomania, aplasia cutis, congenita triangular alopecia, telogen effluvium, and primary scarring alopecia (Table 2).2

Table 2. Differential diagnoses of patchy and diffuse alopecia areata.2

| DD Patchy alopecia areata | DD Diffuse alopecia areata |

| Children/adolescents | |

| Tinea capitis | Loose anagen hair syndrome |

| Trichotillomania | Telogen effluvium |

| Temporal triangular alopecia (N. Breuer) | Congenital hypotrichosis |

| Adolescents/adults | |

| Mucinosis follicularis | Telogen effluvium |

| Alopecia syphilitica | Female pattern hair loss |

| Scarring alopecia, such as CDLE, lichen planopilaris | Drug induced alopecia (antiproliferative, etc.) |

CDLE, chronic discoid lupus erythematosus; DD, differential diagnosis.

Trichoscopy

Trichoscopic features of AA are yellow dots and black dots (Figure 1 A), broken hairs, “exclamation point” hairs (tapered hairs; Figure 1 B), color-transition sign (black distal end advancing to white proximal end), and short vellus hairs (Figure 1 C).4,5

Figure 1. Trichoscopic findings in alopecia areata. (A) Yellow dots (yellow circles) are highly sensitive, but not a specific marker for alopecia areata, as they are associated with other hair loss conditions, such as androgenetic alopecia. Black dots, also shown, are pigmented hairs, broken or destroyed at scalp level. (B) Exclamation point hairs have a thin, hypopigmented proximal end, and a thicker distal end, observable during the acute progressive phase of alopecia areata. (C) Short vellus hairs are thin hairs that mark active disease, or initial response to therapy, in alopecia areata. All photos from DermNet, NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 New Zealand (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 NZ)

Several trichoscopic findings – rather than a single feature – are required to establish a diagnosis of AA:2,4,5

- The presence of yellow dots and short vellus hairs can support the diagnosis of alopecia areata

- Black dots, exclamation point hairs, and broken hairs are also associated with active AA

- Short vellus hairs are observable in the initial stages of hair regrowth after treatment

Histopathology of alopecia areata

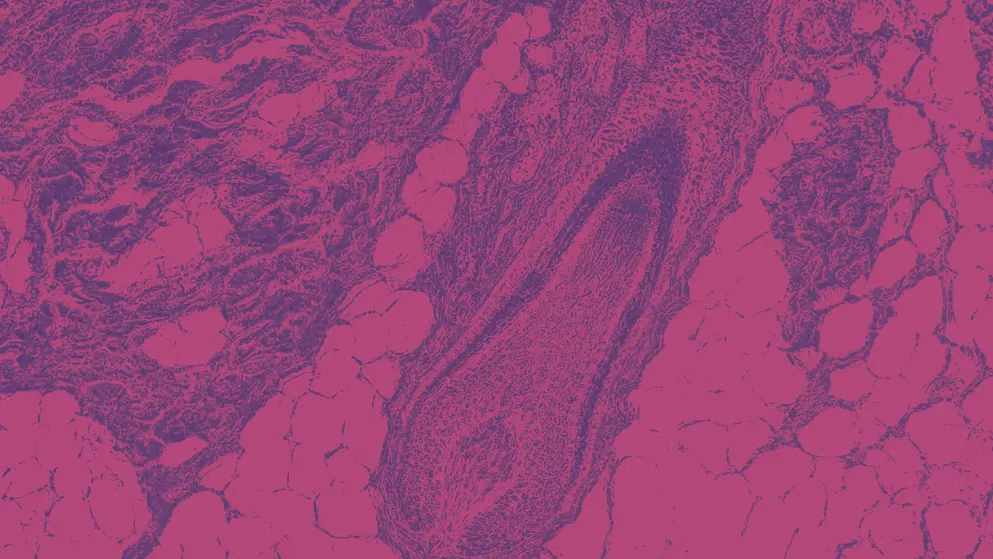

Histopathologic examination can support an AA diagnosis and inform disease staging (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Histopathologic features of intense perifollicular fibrosis in a woman who had circumscribed patches of alopecia areata for 2 months.6 Figure used under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0).

Collapsed fibrous hair root sheath residues (non-sclerosing fibrous tracts) are commonly observed in AA.2 AA may also be distinguished by a peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrate, referred to as a “swarm of bees,” which is a pattern of inflammation observed in the peribulbar region of anagen hair follicles. This feature can also be used to stage the disease.2

Tools for assessing alopecia areata

Clinicians typically use the SALT score to assess the severity of hair loss in four quadrants (left, right, front, and back) and response to treatment (Figure 3 A). A baseline SALT score of >25% is considered severe AA. An improvement of 50–90% in the SALT score is considered a successful response to treatment. Modified SALT II is a refined score that divides the scalp into 1% areas (Figure 3 B). SALT I and SALT II scores rely on visual assessment without documenting specific areas of hair loss.5

(A)

(B)

Figure 3. SALT I and SALT II assessment measures for alopecia areata.3 (A) The SALT score is calculated across four scalp quadrants and then summed to produce the final score. (B) Modified SALT II Visual Aid and computation of ALODEX score density for each 1% of scalp area. Density is scaled from 0–10 according to the percentage of terminal hair loss (100% hair loss = 10; no hair loss = 0). Density values assigned to each 1% area within a scalp quadrant are summed, then divided by the maximum grade of hair loss for that quadrant. The sum of each quadrant’s score is the ALODEX score.3 ALODEX, Alopecia Density and Extent; SALT, Severity of Alopecia Tool.

The Alopecia Areata Progression Index (AAPI) can be used in place of SALT scoring. AAPI incorporates the hair pull test and trichoscopy to quantify disease activity in addition to scalp hair loss.7

Hair loss in other regions of the body can be assessed with the Brigham Eyebrow Tool for Alopecia Areata (BETA), the Brigham Eyelash Tool for Alopecia Areata (BELA), and the ALopecia BArbae Severity (ALBAS) score.7

Sole reliance on SALT and other severity assessment tools for initial clinical observation can result in inaccurate evaluation; this is a noted problem for skin of color populations with AA, in part due to their underrepresentation in literature informing assessment tools and clinical practice.8 This underlines the importance of thorough patient history (including possible culture-specific hair practices), trichoscopy, and biopsy for improving both diagnosis and the accuracy of severity assessment.8,9

Prognosis of alopecia areata

Certain clinical features can be predictors for AA progressing to alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis. These include:

- Onset of AA before puberty3

- Family history of AA3

- Atopy (atopic dermatitis, asthma, or hay fever / allergic rhinitis)3

- Autoimmune diseases (thyroid disease, rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, or celiac disease)3

- Lifestyle factors (obesity, smoking, and alcohol consumption)10

References

- Aldhouse, 2020. "'You lose your hair, what's the big deal?' I was so embarrassed, I was so self-conscious, I was so depressed": A qualitative interview study to understand the psychosocial burden of alopecia areata. https://www.doi.org/10.1186/s41687-020-00240-7

- Lintzeri, 2022. Alopecia areata – Current understanding and management. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/ddg.14689

- Olsen, 2018. Objective outcome measures: Collecting meaningful data on alopecia areata. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.048

- Pratt, 2017. Alopecia areata. https://www.doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.11

- Waskiel, 2018. Trichoscopy of alopecia areata: An update. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.14283

- Lekhavat, 2023. Histopathological diagnosis of alopecia clinically relevant to alopecia areata. https://www.doi.org/10.33192/smj.v75i2.260753

- Darchini-Maragheh, 2025. Assessment of clinician-reported outcome measures for alopecia areata: A systematic scoping review. https://www.doi.org/10.1093/ced/llae320

- Balazic, 2023. Minimizing bias in alopecia diagnosis in skin of color patients. https://www.doi.org/10.36849/JDD.7117

- Vañó-Galván, 2023. Physician- and patient-reported severity and quality of life impact of alopecia areata: Results from a real-world survey in five european countries. https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-01057-0

- Minokawa, 2022. Lifestyle factors involved in the pathogenesis of alopecia areata. https://www.doi.org/10.3390/ijms23031038

Treatment

Several pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical treatments for alopecia areata (AA) are used in clinical practice, with varying effectiveness and tolerability.

Patient advocate Lynn Wilks describes her lived experiences with a range of AA treatments. View transcript.

Treatment for alopecia areata

Individualized treatment for people with AA is informed by several factors, including age, AA severity, duration, and comorbidities. No single therapeutic option is universally recommended.1

Pharmaceutical treatments for alopecia areata

Topical and intralesional corticosteroids

Topical steroid lotions, foams, and shampoos are recommended for limited patchy AA to hasten hair regrowth. Topical agents include:

- Clobetasol propionate 0.05% foam twice daily on 5 consecutive days per week with or without occlusion

- Mometasone furoate 0.1% twice daily on 5 consecutive days per week for 6 months

Treatment should be continued for at least 3 months but stopped after 6 months if there is no effective response. An occasional complication of topical clobetasol is folliculitis.2,3

Intralesional steroid (ILC) treatment involves subcutaneous injection of a slow-release steroid (hydrocortisone acetate or triamcinolone acetonide) by fine needle injection or micro-needling. Adults with less than 50% scalp involvement can be given triamcinolone acetonide 2.5–10 mg/mL (maximum volume 3 mL per session) as first-line therapy. For the eyebrows, 2.5 mg/mL can be used (0.5 mL for each eyebrow). Triamcinolone acetonide is injected intradermally with a 0.5-inch-long, 30-gauge needle as multiple 0.1-mL injections at 1-cm distances with a microfine disposable insulin syringe. Injections are repeated every 4–6 weeks. If effective, hair regrowth should be observed within 4–8 weeks. Treatment should be stopped if there is no improvement after 6 months.2,3

A frequent, but transient, adverse effect is cutaneous atrophy at the injection site. ILCs are not suitable for rapidly progressive patchy AA, alopecia totalis, or alopecia universalis – as they cannot prevent disease development at sites that are not injected – or for children <10 years of age with AA.4,5

Systemic corticosteroids

High doses of daily and weekly oral or intravenous prednisolone pulse therapy can result in effective hair regrowth. However, the response may be insufficient for some patients to balance the adverse effects of systemic corticosteroids, and hair growth can be sustained only during treatment.6,7

Severe AA with >30% scalp involvement is often treated with oral or intravenous prednisolone. Four pulses of 300 mg oral prednisolone at 4-week intervals result in cosmetically acceptable hair growth in more than half of treated patients after 2–3 months of therapy.3 High remission rates have been reported with three pulses of 500 mg of intravenous methylprednisolone on 3 consecutive days at 4-week intervals. The best results are obtained by starting intravenous therapy within 6 months of disease onset, but response rates for AT and AU are unsatisfactory.3

JAK inhibitors

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors act on the cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of AA.8 By blocking the transcription of the JAK–STAT pathways, JAK inhibitors impede the inflammatory autoimmune attack on hair follicles, potentially limiting AA-associated hair loss.8

JAK inhibitors are efficacious in randomized trials, resulting in greater hair regrowth – lower Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) scores – when compared with placebo;8 however, the safety of JAK inhibitors is still an evolving topic.9,10 While there is consensus that the common side effects of JAK inhibitors in the treatment for AA include acne and headache, and a potential elevated risk of respiratory tract infection, more serious adverse effects remain a debated issue.9,10

Beyond AA, JAK inhibitors are used to address autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), ulcerative colitis, and Crohn’s disease.9 Data from trials of JAK inhibitors in these other conditions suggest that they may confer an increased risk of cardiovascular events and cancer, although this is not the consensus with a number of trials finding no relationship.9 Of note, the majority of data linking JAK inhibitors with elevated cardiovascular events and cancer risk stem from studies in RA, a disease associated with both cardiovascular disease and cancer risk.9 Systematic reviews focused on people with AA found no increased risk of cancer or cardiovascular events as a result of JAK inhibitor treatment.9 Further research is required to fully understand the risks associated with JAK inhibitors.

First-generation JAK inhibitors affect more than one JAK family member and inhibit multiple cytokines.11 There is one first-generation JAK inhibitor approved in AA – baricitinib – which is an oral reversible JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor approved in the USA, EU, and Japan for adults with severe AA based on the results of the BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE-AA2 trials.11-13

Second-generation JAK inhibitors can specifically inhibit a single JAK family isoform and selectively block the culprit cytokines. The more specific inhibitory effects of second-generation JAK inhibitors may reduce the risk of long-term or serious adverse events.14

There are two second-generation JAK inhibitors approved for use in AA. The first is ritlecitinib, a JAK3/TEC kinase inhibitor used to treat AA in adults and adolescents.14,15 Approval followed the results of the ALLEGRO phase 2b/3 trial, which showed this treatment option to be well tolerated in people with AA, with approximately 20–30% achieving a treatment response by week 24.15 Further study in the open-label phase 3 ALLEGRO-LT trial showed improved responses with longer treatment, with around three-quarters of the participants achieving a treatment response by month 24.14

The other approved (USA only) second-generation JAK inhibitor is deuruxolitinib – a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor approved to treat severe AA in adults. The phase 3 THRIVE-AA1 and THRIVE-AA2 trials showed deuruxolitinib to be an effective option for hair regrowth.16,17 However, at the time of writing, deuruxolitinib remains unavailable due to an ongoing patent dispute.

JAK inhibitors used for severe AA in children have shown promising results, with either complete regrowth, or at least a 50% reduction in SALT.18 Even with long-term oral or intravenous therapy with JAK inhibitors for severe AA, adverse events tend to be minor and reversible. The most reported adverse events include liver transaminase elevation, upper respiratory tract infection, and eosinophilia.18

Contact immunotherapy

Weekly use of topical allergens (dinitrochlorobenzene, squaric acid dibutylester, and most commonly diphenylcyclopropenone) to induce mild contact dermatitis is an effective option for some patients with patchy AA.19 There is significant variation in response rate data (9–87%) but, in general, 20–30% of patients achieve “worthwhile” regrowth.19

However, 62% of patients successfully treated with topical allergens go on to experience further hair loss.19

Some people treated with contact immunotherapy will experience adverse events, most frequently severe dermatitis and transient occipital and/or cervical lymphadenopathy. While less common, individuals may also experience urticaria or vitiligo. Adverse events can persist throughout treatment. There are no long-term side effects associated with contact immunotherapy at time of writing.19

Non-pharmaceutical treatments for alopecia areata

Excimer laser and light treatment

Excimer laser, an ultraviolet laser, can achieve cosmetically acceptable results in many patients with AA. However, closer examination shows that the apparent hair regrowth can be just a thickening of the hair shaft without any increase in the hair count.20

Successful hair regrowth (65% of patients) has been observed with photochemotherapy in all subtypes of AA. Psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA; oral or topical psoralen, local or whole-body ultraviolet light therapy) has been used successfully.20

Cosmetic strategies

Women with extensive alopecia use concealments such as wigs, hairpieces, or bandanas. Men tend to shave their heads or wear a wig. Some patients choose semi-permanent eyebrow tattooing to restore the appearance of their brows.21

Emotional wellness

To help patients adjust to AA, and to set achievable and meaningful long-term goals, physicians should be sensitive to its psychological effects.22-24

In all subtypes of AA, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, hypnotherapy, psychotherapy, and coping strategies can improve patient quality of life and mental health. Patients with high emotional distress should be referred to specialists in the psychosocial field and be supported to develop active coping strategies.25,26

References

- Meah, 2020. The Alopecia Areata Consensus of Experts (ACE) study: Results of an international expert opinion on treatments for alopecia areata. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.004

- Tosti, 2006. Efficacy and safety of a new clobetasol propionate 0.05% foam in alopecia areata: A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01781.x

- Trüeb and Dias, 2018. Alopecia areata: A comprehensive review of pathogenesis and management. https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s12016-017-8620-9

- Kumaresan, 2010. Intralesional steroids for alopecia areata. https://www.doi.org/10.4103/0974-7753.66920

- Arora, 2022. Comparative efficacy of injection triamcinolone acetonide given intralesionally and through microneedling in alopecia areata. https://www.doi.org/10.4103/ijt.ijt_140_20

- Nakajima, 2007. Pulse corticosteroid therapy for alopecia areata: Study of 139 patients. https://www.doi.org/10.1159/000107626

- Yang, 2013. Early intervention with high-dose steroid pulse therapy prolongs disease-free interval of severe alopecia areata: A retrospective study. https://doi.org/10.5021/ad.2013.25.4.471

- Liu, 2023. Janus kinase inhibitors for alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis. https://www.doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.20351

- Dagna, 2025. Assessment of cardiovascular, thromboembolic and cancer risk in patients eligible for treatment with Janus Kinase inhibitors: The JAK-ERA multidisciplinary consensus. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2025.02.021

- Papierzewska, 2023. Safety of janus kinase inhibitors in patients with alopecia areata: A systematic review. https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s40261-023-01260-z

- Lensing and Jabbari, 2022. An overview of JAK/STAT pathways and JAK inhibition in alopecia areata. https://www.doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.955035

- King, 2022. Two phase 3 trials of baricitinib for alopecia areata. https://www.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2110343

- King, 2023. Integrated safety analysis of baricitinib in adults with severe alopecia areata from two randomized clinical trials. https://www.doi.org/10.1093/bjd/ljac059

- Tziotzios, 2025. Long‐term safety and efficacy of ritlecitinib in adults and adolescents with alopecia areata and at least 25% scalp hair loss: Results from the ALLEGRO‐LT phase 3, open‐label study. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/jdv.20526

- King, 2023. Efficacy and safety of ritlecitinib in adults and adolescents with alopecia areata: A randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 2b-3 trial. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(23)00222-2

- King, 2023. American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting. Results from THRIVE-AA2: A double blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trial of deuruxolitinib (CTP-543), an oral JAK inhibitor, in adult patients with moderate to severe alopecia areata.

- King, 2024. Efficacy and safety of deuruxolitinib, an oral selective Janus kinase inhibitor, in adults with alopecia areata: Results from the Phase 3 randomized, controlled trial (THRIVE-AA1). https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2024.06.097

- Yan, 2022. The efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors for alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. https://www.doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.950450

- Pratt, 2017. Alopecia areata. https://www.doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.11

- Healy and Rogers, 1993. PUVA treatment for alopecia areata—does it work? A retrospective review of 102 cases. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb03309.x

- Mesinkovska, 2020. Burden of illness in alopecia areata: A cross-sectional online survey study. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jisp.2020.05.007

- Korta, 2018. Alopecia areata is a medical disease. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.09.011

- Liu, 2016. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among patients with alopecia areata (AA): A systematic review. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.04.035

- Christensen and Jafferany, 2022. Association between alopecia areata and COVID-19: A systematic review. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jdin.2022.02.002

- Matzer, 2011. Psychosocial stress and coping in alopecia areata: a questionnaire survey and qualitative study among 45 patients. https://www.doi.org/10.2340/00015555-1031

- Maloh, 2023. Systematic review of psychological interventions for quality of life, mental health, and hair growth in alopecia areata and scarring alopecia. https://www.doi.org/10.3390/jcm12030964

Developed by EPG Health. This content has been developed independently of the sponsor, Pfizer, who has reviewed the content only for scientific accuracy. EPG Health received funding from the sponsor in order to help provide healthcare professionals with access to the highest quality medical and scientific information, education and associated relevant content.